On October 2nd 2019, the 150th anniversary of Mohandas Gandhi’s birth, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi surprised both his supporters and detractors with a pean to the Mahatma in, of all newspapers, the New York Times.

Mr. Modi heads a government that is ideologically linked to organizations that inspired Gandhi’s assassin and elected, recently, a lady who called Gandhi’s assassin a patriot. Modi’s associates and party leadership did not go beyond duplicitous condemnation of the remark. So, what’s with telling the world, through New York Times, that “India and the World need Gandhi”?

It is easy to dismiss the oped by pointing out the many contradictions between Modi’s governance and Gandhian principles and that’d be a grave mistake. Narendra Modi and Amit Shah have perfected the art of political skulduggery to the point that Machiavelli looks tame in comparison. Modi is playing a longer game here and we should respect that. Only when we respect our opponent would be bother with an intellectual response to defend Gandhi, unmask the real agenda and dismantle the lies. We shall go to Gandhi himself to unmask Narendra Modi.

Majoor Mahajan Singh – The Forgotten Hero(ine)

Modi, to illustrate Gandhi’s ability to bridge “sections of society”, curiously chose to showcase Gandhi’s mediation of an industrial dispute, in 1918, between mill owners in Ahmedabad and mill workers. Modi credits Gandhi with not just bridging the disparate sections of the society but for using a linguistic deftness in naming the trade union he created by uniting words that indicate “the elite” and the “laborer”.

The oped completely air-brushed out of the picture a brave and highly educated woman, Anasuya Sarabhai. Anasuya lost her parents when she was nine, she was raised by an uncle and married off at thirteen. She divorced her husband soon after and went to England to study. In all that she was supported by her brother Ambalal Sarabhai.

Anasuya Sarabhai

Anasuya, during her stay in England, was influenced by Fabianists like Bernard Shaw and Sydney Webb. It is from such association that she learned of fighting for social equity. She was working for the dispossessed since her return to India in 1913, pre-dating Gandhi.

Ambalal Sarabhai who became a mill owner had once helped finance Gandhi’s ashram. During the negotiations of 1918 strike Ambalal joined other mill owners and Anasuya, moved by the plight of the workers, joined hands with Gandhi. It was Anasuya who created Majoor Mahajan Sangh.

Ambalal Sarabhai

Beyond air-brushing Anasuya out of the picture the oped completely hides another larger truth about India’s liberation struggle and the many other movements that happened in that era, including labor movement. Western liberalism and even western notions of rights, race and nationalism influenced the leaders of India on a grand scale.

Why Western Ideas?

Pre-colonial India did not see liberation struggles or emancipation quests or peasant revolts barring some sporadic incidents and any societal impact was rare if any. India’s class based Varnashrama is often credited for that. Everyone knew their place and society was in harmony. Of course that idyllic story has a seedy underbelly. Caste, in short order, became the guiding principle of organization. Varna, that was class based, became indistinguishable with jati, the caste, and with that a society built, not on rights, but on duties, dharma, was born.

Peasants have revolted as early as 5th century B.C.E in the Roman world resulting in changes within Roman society and power structures. Even Chinese history, to include an Eastern example, is punctuated by labor revolts. The Peasant Revolt in 1381 in England remains a topic of interest for academics for how it remade the society. We’ve to literally come to the 19th century to find peasant revolts of such scale and importance in India.

Rabindranath Tagore brilliantly captured the essence of the effect that caste system had, “in her caste regulations India recognized differences, but not the mutability which is the law of life. In trying to avoid collisions she set up boundaries of immovable walls, thus giving to her numerous races the negative benefit of peace and order but not the positive opportunity of expansion and movement. She accepted nature where it produces diversity, but ignored it where it uses that diversity for its world-game of infinite permutations and combinations”.

The idea of an enslaved people craving for liberty and fashioning their own nation is a Judeo- Christian idea building on a Greco-Roman heritage. From the probably mythical Exodus of Jews from slavery to Patrick Henry’s clarion call “Give me liberty or give me death” in the 18th century the idea of a liberated nation is a western idea. When Bal Ganhadhar Tilak said “Swaraj is my birthright” he was echoing Patrick Henry, not Indian heritage.

To be fair to India’s leaders they also adopted the language of the West to speak to the colonizer in a language they’d understand. That said it is time Indians learned how their liberation was born in the crucible of western ideas.

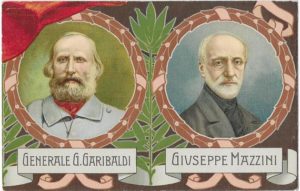

Mazzini, Garibaldi and Indian nationalism

Mazzini, Garibaldi and the Italian nationalism they spearheaded cast a very long and persistent shadow on India’s liberators across a vast spectrum of ideologies.

Bengali nationalist Surendranath Banerjee studied Mazzini and literally became his evangelist and delivered many speeches in Bengal amongst students about Mazzini and Italian nationalism. Amongst the many inspired by Surendranath Banerjee’s speeches were Bipin Chandra Pal and Lala Lajpat Rai. Lajpat Rai wrote that Banerjee’s speeches moved him “to tears” and that he would follow the ideals of Mazzini in the service of the nation.

Vivekananda’s disciple, Sister Nivedita, gave Bhupendra Nath Bose, prior to his imprisonment, 4 volumes of Mazzini’s writing and donated the first volume of Mazzini’s autobiography to young revolutionaries.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s conception of nationalism, Bidyat Chakraborty notes, was “a combination of the Vedanta ideal of the spiritual unity of mankind and the western notions of nationalism as propounded by Mazzini, Burke, Mill and Wilson. Tilak adored Mazzini and Garibaldi.

Subash Chandra Bose admired Mazzini and cited his success as example for India triumphing the divisions and obstacles. Jawaharlal Nehru was captivated by Trevelyan’s trilogy on Garibaldi.

Mazzini’s writings were widely translated by many. Few of them are Jogendranath Vidyabhushan, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, Lala Lajpat Rai (to Urdu), V.V.S. Iyer and Subramania Bharathi.

Can Gandhi be immune to the charms of Mazzini and Garibaldi?

Gandhi, a child of the west……. and east

Of Nehru it is commonly said that he was a westerner who had to learn to become Indian. Gandhi, unlike Nehru, is often thought to be a son of the soil who sprung up from India’s heritage and allowed a few stray pollinations from the West. Truth is Gandhi was as much a westerner as Nehru was or close enough.

Pankaj Sharma sums up Gandhi, “the deepest influences on him were largely European and American”. “He counted Emerson, Thoreau, and John Ruskin as his gurus, borrowing from Ruskin the notion of the dignity of manual labor. His emphasis on duty came from Giuseppe Mazzini.” “Catholic writer G. K. Chesterton helped inspire Gandhi’s main contribution to political theory, “Hind Swaraj” (1909). Gandhi absorbed many ideas osmotically”.

Gandhi’s biographer Ramachandra Guha identifies how Gandhi, unable to find “precedents in Indian traditions of boycott and protest”, turned to the vocabulary of British Non-conformists.

Later he borrows the vocabulary and ideas of H.D. Thoreau to fashion “Civil Disobedience”. Of Mazzini, Gandhi wrote to his son Manilal, “what was possible for Mazzini and Garibaldi is possible for us”

The idea of duty that Gandhi formulated as his guiding principles did not come merely from Bhagavad Gita but from Mazzini and John Ruskin and Socrates too. Gandhi read Plato’s ‘Apology’, the famous philosophical tract where Socrates addresses his Athenian tormentors, in jail. So thrilled was he by that tract that he translated it to Gujarati and serialized it in his newspaper titled, “Ek satyavirni katha” (‘Story of a true soldier’).

The animosity that Gandhi had towards industrialization was borrowed heavily from Western thinkers who excoriated industry and technology. Summarizing Ruskin’s book Gandhi wrote that he learned, “that a life of labor, that is the life of the tiller of the soil and the handicrafts man, is the life worth living”. He translated Ruskin’s book to Gujarati, titled “Sarvodaya”.

The influence of Tolstoy, particular the latter day moralist than the novelist, had on Gandhi through his letters and his “The Kingdom of God is in you” was immense. Religion was always an intensely private vocation for Gandhi. This is a little understood part of Gandhi. While he suffused religion in his politics he was not, like Tilak, for politicizing religion.

Thomas Weber cautions that these Western influences “only added to what he was discovering in his own religion”. One could fairly accuse Gandhi of confirmation bias for seeking out, amongst vast swathe of literature, only those that’d validate his Hindu beliefs. That’d be unfair because Gandhi did seek across a vast landscape and he picks intellectual giants from various cultural and intellectual milieu for valid reasons. Take, for example his vegetarianism.

Religion was the motivator for Gandhi’s vegetarianism but he always felt that beyond religious proscription there was no valid reason to avoid non-vegetarian and he actually felt eating meat might help Indians be physically stronger. Though he was influenced by the Vegetarian movement in England and by Henry Salt he continued searching for making his diet healthy and vegetarian. His search led him to George Washington Carver, an American botanist in Iowa.

Gandhi corresponded with Carver between 24th February 1929 and 27th July 1935 on questions relating to diet.

Hinduism gave Gandhi his core beliefs but it was the West that supplied him the intellectual ballast to fortify his principles. He was a child of the West and East, in that order.

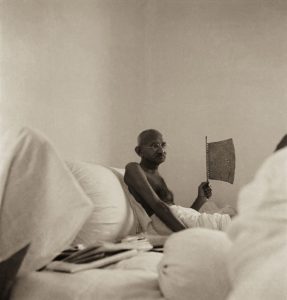

Gandhi and the power of ‘no’

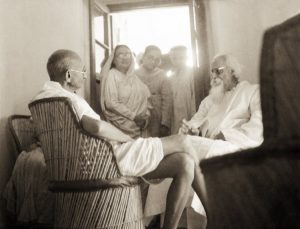

Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore had a very curious relationship. Tagore called Gandhi, 8 years his younger, ‘Mahatma’ and Gandhi referred to Tagore as ‘Gurudev’ and ‘Great Sentinel’ and often ‘The Poet’. The correspondences between Gandhi and Tagore are noted, besides the personal correspondences, for the public debate they had through newspaper columns. Two important debates concern the nature of non-cooperation movement and the promotion of the charkha.

Tagore was alarmed that the non-cooperation movement was at it core a spirit of rejection and that was anathema to the spirit of cooperation that the poet longed for between civilizations. He also worried that a rejection of western education would harm Indians.

Gandhi, writing in his newspaper Young India, allaying Tagore’s fears wrote:

“I want the cultures of all the lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any….

I would have our young men and young women with literary tastes to learn as much of English and other world-languages as they like….

I would not have a single Indian to forget, neglect or be ashamed of his mother- tongue, or to feel that he or she cannot think or express the best thoughts in his or her own vernacular”.

Refuting Tagore’s characterization of non-cooperation as rejectionist Gandhi cites the principle Upanishadic formulation of “it is not”, ‘Neti, Neti’ and then in brilliant prose offers defense of saying ‘no’ to a government.

“We had lost the power of saying ‘no’. It had become disloyal, almost sacrilegious to say ‘no’ to the Government. This deliberate refusal to cooperate is like the necessary weeding process that a cultivator has to resort before he sows…Non-cooperation is the nation’s notice that it is no longer satisfied to be in tutelage.”

We don’t need a second coming of Gandhi. He taught us and taught us well to carry on without him. The question Mr. Modi is how does your government and your brigade of supporters react to those who say “no”?

Modi cited Gandhi’s use of charkha as a unifying symbol. Probably the sharpest exchanges between Gandhi and Tagore happened over what the Poet called ‘The cult of the charkha’. Tagore protested that a singular promotion of charkha would promote a sameness, not address the economic impoverishment and is being adopted as a symbol by a country steeped in a practice of worshipping symbols. Gandhi, appropriately, pushed back that the poet functions on a different plane and argued that spinning is an activity that all of India could unite on as every human being had to clothe himself or herself.

Modi, who dresses in designer clothes and indulges in symbolic spinning that is practically a sham enactment, is evidence that Tagore’s fears of the charkha being reduced to an empty symbol came true.

Gandhi and State

Narendra Modi wrote in his oped, “When the world spoke about rights, Gandhi emphasized duties”. This is a totally warped understanding of Gandhi and it is for an important reason that Modi chose to present this but before that we need to ask what was Gandhi’s idea of State.

Anthony Parel’s essay “Gandhi and State” outlines Gandhi’s idea of the reason of state, the state he did not want and the state he wanted.

The theory of the reason state, in Gandhi’s time, prevalently held that the state can “make the claim that its interests are morally superior to any other human interest”. Gandhi while not “denying the importance of national interest to state conduct” could not accept that national interest “be the sole consideration in decision making”. “There are spheres in the individual’s life that are closed off to the state” and “obedience is owed the state only when it acts ethically”. A religion based state, to Gandhi, violated the limits of each and was unacceptable.

While Gandhi cautioned against an aggressive state he certainly presented the state as a guardian of rights. Gandhi’s life was all about agitating for rights and this is conveniently airbrushed by Narendra Modi for insidious reasons that I’ll detail later.

Parel cites the Purna Swaraj declaration of 26th January 1930 authored by Gandhi (some claim it was edited by Jawaharlal Nehru) and the subsequent “Resolution on Fundamental Rights and Economic Changes” passed in 1931 as Gandhi’s ideas of a State as guarantor of Rights. Both documents curiously bear a distinctly Jeffersonian stamp.

The Declaration for Complete Independence said:

“We believe that it is the inalienable right of the Indian people, as of any other people, to have freedom and to enjoy the fruits of their toil and have the necessities of life, so that they may have full opportunities of growth. We believe also that if any government deprives a people of these rights and oppresses them the people have a further right to alter it or to abolish it.”

The resolution on fundamental rights, also called Karachi Resolution (1931) literally reads like Bill of Rights of American constitution. It called for any Swaraj government to provide for: freedom of association, freedom of speech and press, freedom of conscience and free profession and practice of religion subject to public order and morality, right to keep and bear arm, right of labor to form unions, a living wage for industrial workers, adult suffrage, free primary education and other rights.

The Karachi resolution is a blueprint for a state as guarantor of rights. The “right to bear arms” is perhaps the most interesting for not merely echoing America’s now notorious Second Amendment but also for the fact it emphasizes a little known part of Gandhi’s life. Gandhi agitated for the right to bear arms by Indians. The resolution also spoke of reducing military expenditure, not the abolition of military. Gandhi was more realistic about war and military than is commonly understood.

Modi was emphasizing duties because it is a fetish of the Hindutva philosophy that India, unlike Western civilization, was built as Dharmic civilization and not a society based on rights. It is not uncommon to find the Hindutva front arguing for the merits of Varnashrama, that insidious grotesque system of yore that served a privileged few at the expense of many. One may argue that Gandhi, too, articulated a support for varnashrama. Gandhi’s idea of varnashrama was, to be blunt, loopy and trying to avoid the ills that happened it was nothing but a shell but that is not what Modi’s brigade wants.

Einstein and Gandhi

V.A. Sundaram (Vellalore Annaswamy Sundaram), a follower of Gandhi, was deputed by Gandhi as a sort of ambassador to Europe to spread his message prior to attending the Second Round Table Conference in England in 1931. Sundaram met many including Mussolini, Pope Pius, Stephen Spender, Andres Maurois and Albert Einstein. Einstein wrote a note for Gandhi and passed it through Sundaram. The note, dates are conflicted but around Sep-Oct 1931, paid a tribute to Gandhi’s advocation of non-violence. Gandhi replied back from London and hoped they could meet.

Later in 1939 Einstein contributed to a tribute that S.Radhakrishnan compiled for Gandhi’s 70th birthday. Einstein said Gandhi’s influence on the civilized world may outlast our admiration of brute force. In a statement he prepared for the same occasion and later published in his book, ‘Out of my later years’ (1950) Einstein offered the immortal eulogy, “generations to come will scarcely believe that a being such as this walked in flesh and blood upon the face of this earth”.

A physics professor from Ambala wrote to Einstein, after Gandhi’s death, criticizing Gandhi’s rejection of technology. Einstein in his reply accepts that as fair criticism of Gandhi but draws attention to the larger message of the Mahatma and asked if it is fair to kill a man because he has a different opinion. The professor then writes two more letters calling Gandhi a Hitler in one and justifying his murder in another. Einstein did not reply to to those.

Dubious claims and the bogus Einstein challenge

The oped claims that India is vastly eliminating poverty whereas in reality the country is facing a deep economic crises and the government, after failing to make people believe otherwise, is rolling out one knee jerk prescription after another to stop the decline. The decline started with the disastrous demonetization that caused untold misery to millions of poor. The oped also claims that India’s sanitation efforts are getting global attention but fails to mention that even today in India men get down into sewers and clean human excreta with hands and many die in that process.

Dubious claims aside we’ve to ask why did Modi bother to write that oped that too in the New York Times. If anything Modi should’ve written in Hindi and in an Indian newspaper. It is in India that Gandhi is most reviled today and in large measure due to the Islamophobia fanned by Hindutva brigade which considers Gandhi as a stooge of Muslim India. Modi is playing a game here, trying to court the West and he finds Gandhi a useful mask to use.

Beyond courting the West using Gandhi Modi is also trying to use Gandhi as a trojan horse to dress his Hindu nationalism as Gandhi’s nationalism. Modi’s nationalism threatens, ostracizes and even kills those who say ‘no’. Modi recently lamented that some are scared hearing ‘Jai Shri Ram’. When Gandhi said ‘Hey Ram’ no Indian felt threatened.

By quoting Gandhi that he was as much an internationalist as he was a nationalist Modi was implying that nationalism was a credo of Gandhi too. True, but the nationalism that Modi espouses has no space for internationalism. Rather, Modi’s nationalism is crude, chauvinistic and parochial in manufacturing pride, based on dubious theories, about India’s heritage.

Gandhi, unlike Modi, was a lifelong seeker of knowledge from all corners of the world. The Hindutva philosophy completely disavows learning from anything or any one outside India, especially from the West. Modi and his philosophy are insular and philistine. Gandhi was neither.

It is not without reason that Modi chose to highlight Gandhi’s role in resolving a labor dispute to highlight building bridges rather than Hindu-Muslim unity or Gandhi’s campaign against untouchability that brought out reform instincts amongst many upper castes as examples. Those two examples would’ve unsettled Modi’s base at large and particularly his upper caste base today.

Rarely was a human life lived amidst such turmoil so devoid of hatred and malice as Gandhi’s was. Gandhi wanted to protect cows but not with the brute force of the state and much less the muscle of rampaging mobs that kills Muslims. Whether it is English viceroys who jailed him or Ambedkar his harshest foe or members of upper caste who tried to kill him or Muslims of Naokhali or Suhrawardy or even the Christian missionaries that he disagreed with there was no one with whom the Mahatma nurtured a malice.

Modi, his cabinet and the entire Sangh Parivar make no bones about eliminating Muslim immigrants in border states and threatening India’s Muslim citizenry. Not a day passes without a senior leader of the party or even a minister threatening minorities or dissenters. No modern state, including Jawaharlal Nehru’s, could be called a Gandhian state but Modi’s state is the very anti-thesis of every value of Gandhi.

Einstein wondered if future generations would believe that Gandhi lived in flesh and blood because of the improbable nature of his life. Gandhi, C.E.M. Joad wrote, inspired many to cultivate the courage to be beaten to pulp without raising a single finger in defense.

Modi flings down a bogus challenge asking “thinkers, entrepreneurs and tech leaders to be at the forefront of spreading Gandhi’s ideas through innovation”. That is the silliest interpretation of Einstein’s eulogy and an insult to Gandhi. But true to his word Modi gathered the glitzy Bollywood crowd and discussed spreading Gandhi’s ideas.

Meanwhile a group of Gandhi’s admirers paid high tribute to Gandhian Krishnammal Jagannathan who has done admirable service amongst the underprivileged in caste riot torn area of Tamil Nadu. The occasion was the release of a Tami version of an oral biography of the Gandhian couple by Laura Coppo.

Finally, it is highly doubtable that Modi wrote that oped. It was possibly ghost written and it was, stylistically speaking, poorly written. An article English that too in New York Times for an American audience is such a Nehruvian act Mr. Modi. Tsk Tsk.

References

- Narendra Modi’s oped in New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/02/opinion/modi-mahatma-gandhi.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_peasant_revolts

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anasuya_Sarabhai

- https://www.thebetterindia.com/73140/anasuya-sarabhai-labour-movement-ahmedabad/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abhinav_Bharat_Society

- https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/74210/14/14_chapter%205.pdf

- Pankaj Sharma on Gandhi: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/10/22/gandhi-for-the-post-truth-age

- E-Book of Gandhi-Tagore correspondence : “The Mahatma and the poet” https://mkgandhi.org/ebks/the-mahatma-and-the-poet.pdf

- E-Book of Hind Swaraj : https://jmu.edu/gandhicenter/wm_library/gandhiana-hindswaraj.pdf

- Purna Swaraj Declaration : https://www.constitutionofindia.net/historical_constitutions/declaration_of_purna_swaraj__indian_national_congress__1930__26th%20January%201930

- Karachi Resolution (Fundamental rights) : https://www.constitutionofindia.net/historical_constitutions/karachi_resolution__1931__1st%20January%201931

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Purna_Swaraj

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhupendra_Nath_Bose

- Tagore’s essay on Nationalism (1917) : http://tagoreweb.in/Render/ShowContent.aspx?ct=Essays&bi=72EE92F5-BE50-40D7-8E6E-0F7410664DA3&ti=72EE92F5-BE50-4A47-2E6E-0F7410664DA3

- Correspondence between Gandhi and George Washington Carver : https://iowaculture.gov/history/education/educator-resources/primary-source-sets/population-and-land-use/letter

- Phiroze Vasunia’s article “How Gandhi used Socrates” : https://www.ndtv.com/opinion/how-gandhi-used-socrates-738600

- Phiroze Vasunia “Gandhi and Socrates” essay : https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1510023/1/Vasunia_AAM_gandhi_and_socrates.pdf

- V.S. Iyer and Mazzini : https://puthu.thinnai.com/?p=2302

- Subramaniya Bharathi poem on Mazzini : https://ilakkiyam.com/bhrathiyar-padalgal/58-desiya-geethangal/4065-maginiyin-sabatham-pirathikillai

- Gandhi before India – Ramachandra Guha

- Gandhi: The years that changed the world (1917-1948) – Ramachandra Guha

- The Cambridge Companion to Gandhi – Edited by Judith Brown and Anthony Parel

- Gandhi: HInd Swaraj and Other Writings – Edited by Anthony Parel

- The essential Gandhi: An anthology – Edited by Louis Fischer

- Einstein’s letter to Gandhi : http://www.lettersofnote.com/2011/11/when-einstein-wrote-to-gandhi.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/V._A._Sundaram

- Einstein and the Indian Minds: Tagore, Gandhi and Nehru by Rasoul Sorkhabi : https://currentscience.ac.in/Downloads/article_id_088_07_1187_1191_0.pdf

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/use-your-reach-to-popularise-gandhigiri-pm-modi-%20to-filmstars/articleshow/71669285.cms