Heraclitus prophetically proclaimed that no man ever steps in the same river twice. He argued that neither the constantly flowing river, whose water changes with each passing moment, nor the man who crosses it remains the same. A cinephile, a true cinephile, can see his reflection in the same river of Heraclitus. The growing world of life-experiences and understanding of the medium doesn’t allow the waking mind to see the same film twice. Like new-born dew, the film decants on you as a new incarnation of the same soul. Till the time end credits start to roll out, the mind grasps something new which had slipped through your fist in the past viewings. Even though you are watching the same known film, thus, you are not watching the same film. The experience of re-watching Béla Tarr’s The Turin Horse is a standing testimony to it.

The film begins with the famous tale of Friedrich Nietzsche witnessing the whipping of a horse while traveling in Turin, which allegedly pushed him towards a serious mental illness that made him bed-ridden and speechless for the next eleven years until his death – and it ultimately descends into the heaviness of everyday life. Fingers will fall short to count the number of films that tried to do the same. But this bleak saga struck as the celestial comet not because of its subject matter, but what Tarr did with it.

The bitter truth is, there are very few directors who can deftly punctuate the ears of cinema with telling silence. In this film, Bela Tarr has arranged an exhibition on how to finesse that long-lost art. After the initial narration of the Nietzsche tale, there is no human communication for the first 21 minutes. The lead characters, the father and the daughter, are ensconced within the drudgery that the abysmal life has brought to them. They only speak when it’s unavoidable. They only move when they can’t stay motionless.

Amidst this melancholic vibe, we see the soul-sapping grinding of life. We see the moments of daily chores, with the regularity of a pendulum, like going to the well and filling the buckets with water; or keeping stocks of the wood by chopping it. But what adds a watermark to this daily grinding is the vision of the man sitting behind the camera. As someone who understands the all-looking power of stasis, Tarr has converted a camera into a microscope. He doesn’t just give the hint of all those activities. He shows them in complete detail, with their natural pace. The camera follows the girl from behind – including her long walk towards the well and her act of filling the buckets with water – till she again comes back to her house. It took me long to understand that such long takes are shoveling me in the closest possible proximity with hardships of the characters, letting me feel unadulteratedly what they are feeling. Thus, the declaration from Lav Diaz that long take is my ideology.

However, to accentuate the harshness of the living conditions, Béla Tarr has used the instrument of nature, probably in a way that is unheard and unseen in the history of cinema. Throughout the running-length of 150 minutes, we see and hear a strong gale, making the silence in the house becomes starkly audible. Moreover, the terrifying sound and the sight of a ragging gale put the daily activities like feeding the horse and going to well for water in the light of Herculean efforts. Consequently, you feel more about the heaviness of their existence. Tarr has gone further by showing 3-4 times that characters are sitting silently in a chair and gazing through the window where floating leaves are getting caught up in the intense whirlwind. Cinema is yet to see a superlative example of how nature becomes the character itself and extrapolates the desired psychological impact.

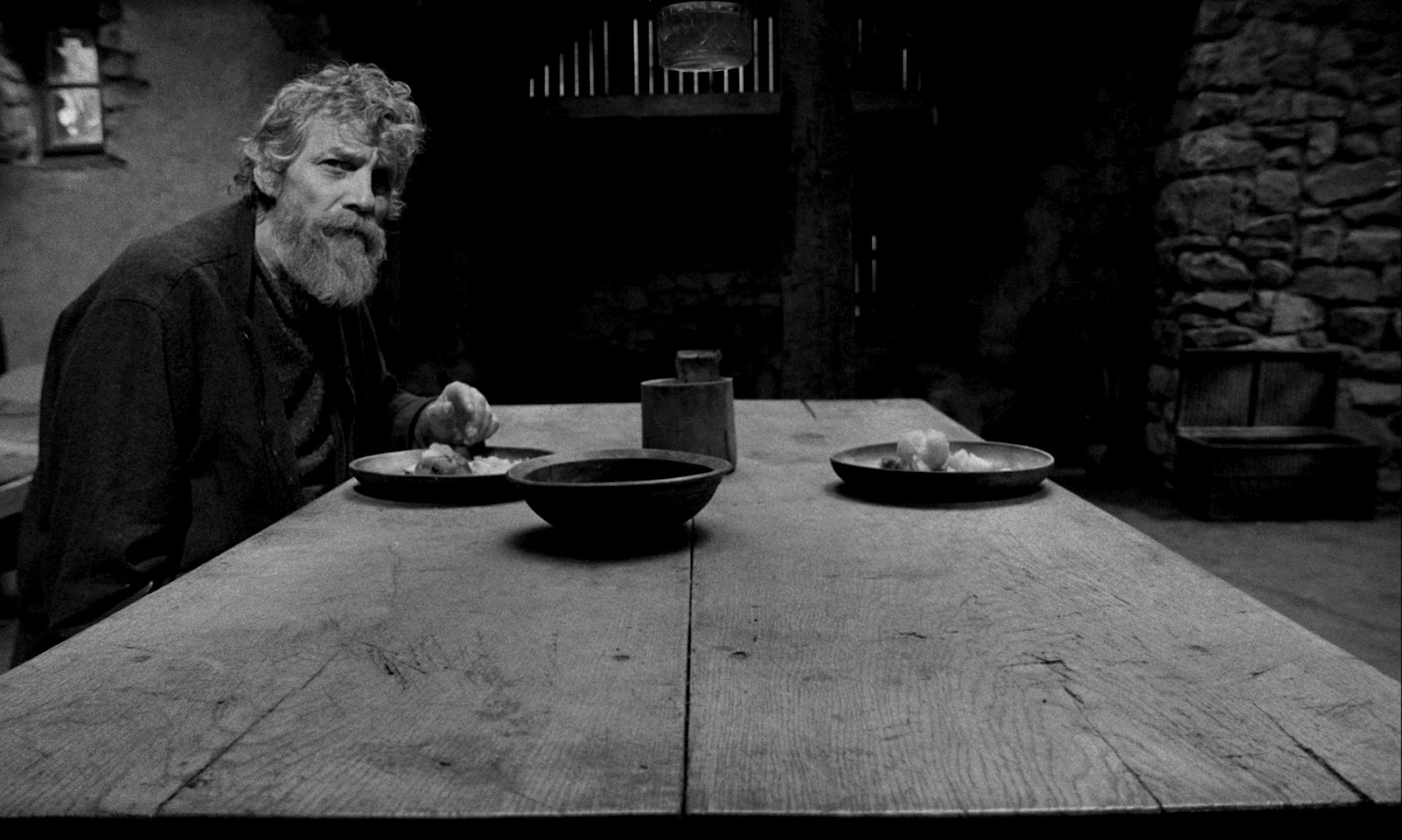

But the real masterstroke, which I will remember till I wear soil, comes with Tarr’s unique way of showing that life is a repetition of repetition. In the entire film, we see that the girl and the father are eating boiled potatoes all the time. Even the call for dinner and lunch is the same: girl’s expressionless utterance – “It’s ready.” Every time we hear this, we see them eating. The consummate deliberation of the scene transformed the innocuous potato into a metaphor for their repetitive lives. To let this visual metaphor consume you ceaselessly, the film ends with an image where they are eating potatoes.

Now, the moot point is, potatoes are as visible as the stupidity of mankind. But it takes the percipience of Tarr to metamorphose them into an everlasting symbol, a trope, of a downtrodden life. And that’s precisely why every book that will intend to decipher the magic, art, and craft of cinema will have a chapter or at least a fleeting paragraph that salutes the maestro from Hungary…!

*

The author of this article could be contacted via prasad_dhamdhere@yahoo.com