You have been watching tennis for many years. You remember Martina Navratilova and Chris Evert, McEnroe and Conners on the wane; Boris Becker and Stefan Edberg, Steffi Graf and Gabriala Sabatani on the rise. Seles and Hingis. Agassi and Sampras. Even Ivanisevic and Jana Novotna. Federer and Nadal. Djokovic and Murray. You have moments and memories from their matches. But you ask yourself, how much do you remember of the greatest woman player of our era, and probably of all time. Or about her illustrious sister. Honestly, very little. Yes, you know, she has been winning match after match; slam after slam. More than Federer. More than Sampras. More than Nadal. More than Graf. But those are numbers. Not moments. Why? Is it because she lacks charm? What charm did Sampras have, or Nadal? Is it because she has played a hard-hitting game? Don’t most modern players do the same, with the exception of Roger Federer at his brilliant best? [This part was written before this year’s US Open Finals. Now you may have moments to remember from that match. Even now, you may not have watched the match live, but caught those moments on youtube. But in the context of those moments, these lines have chosen to remain unchanged. If you think what you saw was a one-off incident of bad behavior, and Serena crying sour grapes and Serena justifying bad behavior and Serena seeking license for future bad behavior, this piece may urge a rethink. You may want your champions to be made of spotless white material; however, well, it is not that Serena is spotless but Serena is not white]

Ralph Ellison starts his novel, Invisible Man, with these lines:

“I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me.

Nor is my invisibility exactly a matter of a bio-chemical accident to my epidermis. That invisibility to which I refer occurs because of a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact. A matter of the construction of their inner eyes, those eyes with which they look through their physical eyes upon reality.”

You are wondering if it is the phenomenon of the ‘Invisible Woman’ that has made you overlook Serena Williams and Venus Williams, and not carry any significant memories about the matches involving either of them. Black champions in a game dominated by Whites. Were you inflicted by racial bias? Maybe, not. You would even like to consider yourself to be vehemently anti-racist. Yet, you may admit, maybe with shame, that you too had probably become conditioned to equate grace with White grace, and charm with White charm, and not really appreciate the greatness of these two wonderful black women, when they were at their peak.

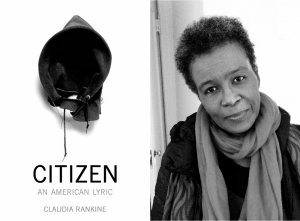

More than anybody, the poet, Claudia Rankine, makes you see the invisible men and women in her book, Citizen: An American Lyric. “What doesn’t belong with you won’t be seen,” writes Rankine.

The wanton obliviousness to the invisible is what has perhaps helped the proudly liberal and democratic West to practice racism, genocide, plunder, slavery and segregation with a clean conscience and a sense of moral superiority, even while it fought to liberate the Jews from Hitler or Afghans and the Vietnamese from the Communism, or Africa and India from superstition and rituals.

Is it a book of poetry? Ah, yes. But the line between poetry and prose is so completely blurred and erased, that many of the poems lay claim to the status of poems sheerly on the weight of the content, and shedding all pretenses of form. If modern poetry pushed out and rewrote the prosodic boundaries around poetry, newer poets like Claudia Rankine completely break free of all restraints. A lyrical essay on Serena Williams and a wonderfully sequenced assortment of quotes to bring out the story of Zinedine Zidane in World Cup 2006, sit comfortably with a series of poems and reminiscences.

She starts with everyday occurrences in ‘your’ life.

In line at the drugstore it’s finally your turn, and then it’s not as he walks in front of you and puts his things on the counter. The cashier says, Sir, she was next. When he turns to you he is truly surprised.

Oh my God, I didn’t see you.

You must be in a hurry, you offer.

No, no, no, I really didn’t see you.

Then Rankine turns her sharp poetic gaze towards celebrities like Serena Williams and Zinedine Zidane. You had not learnt to look at their successes and lapses through the prism of race.

You knew the head-butt by Zinedine Zidane that costed the French team another World Cup victory. But you could never fathom the pressure he was under. The abuses that were thrown at him.

“Do you think two minutes from the end of a World Cup final, two minutes from the end of my career, I wanted to do that?” she quotes Zinedine Zidane. “What he said “touched the deepest part of me.””

“Big Algerian shit, dirty terrorist, nigger,” Claudia puts together the accounts of lip readers responding to the transcript of the World Cup.

“Every day I think about where I came from and I am still proud to be who I am…” asserts Zidane.

No one is free.

For all that he is, people will say he remains for us an Arab. “You can’t get away from nature.” (Frantz Fanon)

Even more glaring but unseen has been the racial bias encountered by Serena Williams. You wonder how many of us remember this incident in 2004, which Claudia narrates with such rancour. Even if you do, how many of us could see the racist tinge on that incident.

“The most notorious of Serena’s detractors takes the form of Mariana Alves, the distinguished tennis chair umpire. In 2004 Alves was excused from officiating any more matches on the final day of the US Open after she made five bad calls against Serena in her semifinal match-up against fellow American Jennifer Capriati. The serves and returns Alves called out were landing, stunningly unreturned by Capriati, inside the lines, no discerning eyesight needed. Commentators, spectators, television viewers, line judges, everyone could see the balls were good, everyone, apparently, except Alves. No one could understand what was happening. Serena, in her denim skirt, black sneaker boots, and dark mascara, began wagging her finger and saying “no, no, no,” as if by negating the moment she could propel us back into a legible world. Tennis superstar John McEnroe, given his own keen eye for injustice during his professional career, was shocked that Serena was able to hold it together after losing the match.

Though no one was saying anything explicitly about Serena’s black body, you are not the only viewer who thought it was getting in the way of Alves’s sight line. “One commentator said he hoped he wasn’t being unkind when he stated, “Capriati wins it with the help of the umpires and the lines judges.” A year later that match would be credited for demonstrating the need for the speedy installation of Hawk-Eye, the line-calling technology that took the seeing away from the beholder. Now the umpire’s call can be challenged by a replay; however, back then after the match Serena said, “I’m very angry and bitter right now. I felt cheated. Shall I go on? I just feel robbed.”

Serena is meted out more such decisions. A bad line call at a crucial juncture. A harsh penalty at another critical moment. She gets furious. She swears. She breaks rackets. She faces a hefty fine. She is put on a two-year probationary period. (And outside the book, she gets picked for wearing a full-length black catsuit, to counter her post-maternity issues. And yes, the infamous US Open incidents now.) She asks a referee if ‘she is trying to screw her again.’ Claudia highlights the use of the word ‘again’, which ‘returns her viewers to other times calling her body out.’

“Again Serena’s frustrations, her disappointments, exist within a system you understand not to try to understand in any fair-minded way because to do so is to understand the erasure of the self as systemic, as ordinary. For Serena, the daily diminishment is a low flame, a constant drip. Every look, every comment, every bad call blossoms out of history, through her, onto you. To understand is to see Serena as hemmed in as any other black body thrown against our American background. “Aren’t you the one that screwed me over last time here?” she asks umpire Asderaki. “Yeah, you are. Don’t look at me. Really, don’t even look at me. Don’t look my way. Don’t look my way,” she repeats, because it is that simple.

Yes, and who can turn away? Serena is not running out of breath. Despite all her understanding, she continues to serve up aces while smashing rackets and fraying hems. In the 2012 Olympics she brought home the only two gold medals the Americans would win in tennis. After her three-second celebratory dance on center court at the All England Club, the American media reported, “And there was Serena … Crip-Walking all over “the most lily-white place in the world…. You couldn’t help but shake your head…. What Serena did was akin to cracking a tasteless, X-rated joke inside a church…. What she did was immature and classless.”

It is true that wrong line calls and poor umpiring decisions are part of every sport. But when a particular player of a particular color, ‘thrown against a sharp white background’, is repeatedly at the receiving end, you cannot help attributing a racial flavor to it [Serena, now, attributes a gender flavor too]. Why does the rule book have a knack of flinging itself only on you, and often unfairly, you ask. Claudia writes about another farcical incident, when ’the Dane Caroline Wozniacki, a former number-one player, imitates Serena by stuffing towels in her top and shorts, all in good fun, at an exhibition match.’

It’s then that Hennessy’s suggestions about “how to be a successful artist” return to you: be ambiguous, be white. Wozniacki, it becomes clear, has finally enacted what was desired by many of Serena’s detractors, consciously or unconsciously, the moment the Compton girl first stepped on court. Wozniacki (though there are a number of ways to interpret her actions—playful mocking of a peer, imitation of the mimicking antics of the tennis player known as the joker, Novak Djokovic) finally gives the people what they have wanted all along by embodying Serena’s attributes while leaving Serena’s “angry nigger exterior” behind. At last, in this real, and unreal, moment, we have Wozniacki’s image of smiling blond goodness posing as the best female tennis player of all time.

If these are the problems faced the by black celebrities, and let us move away from celebrities – you have your own opinions, judgements, biases which are difficult to engage with, Claudia’s poems on the black common man and woman, the invisible folks, are the mainstay of the book. Almost all are written using the second-person pronoun. She shuns the ‘I’. She embraces the ‘you’.

Sometimes “I” is supposed to hold what is not there until it is. Then what is comes apart the closer you are to it.

This makes the first person a symbol for something.

The pronoun barely holding the person together.

Someone claimed we should use our skin as wallpaper knowing we couldn’t win.

You said “I” has so much power; it’s insane.

And you would look past me, all gloved up, in a big coat, with fancy fur around the collar, and record a self saying, you should be scared, the first person can’t pull you together.

Shit, you are reading minds, but did you try?

Tried rhyme, tried truth, tried epistolary untruth, tried and tried.

Elsewhere, she scorns the ‘I’ yet more, ‘Don’t say I if it means so little,/ holds the little forming no one.’ It is not just the I of the invisible that is futile, but that of the visible, the prominent too.

“Listen, you, I was creating a life study of a monumental first person, a Brahmin first person.

If you need to feel that way—still you are in here and here is nowhere.

Join me down here in nowhere.

Don’t lean against the wallpaper; sit down and pull together.

Yours is a strange dream, a strange reverie.

No, it’s a strange beach; each body is a strange beach, and if you let in the excess emotion you will recall the Atlantic Ocean breaking on our heads.”

You feel ‘you’ is a powerful tool. It is no longer a story about somebody else. You have no scope to look away. You have no room to skirt the issues. You are suffering. You are causing the suffering. You are the invisible. But you can’t help seeing yourself. And seeing others in yourself. And seeing yourself in others.

You are the oppressor. You are the oppressed. You have risen up from the downtrodden. You refuse to see your brethren from the earlier times. You are now the elite. Rankine introduces you to a middle aged writer at London, a writer, with what she calls the ‘the face of the English sky—full of weather, always in response, constantly shifting, clouding over only to clear briefly’; a writer, who asks her to write about the riots over the killing of Mark Duggan, a black man [a black man, a husband, a father] shot dead by the police on suspicions of being a drug dealer. The riots led to looting. ‘Whatever the reason for the riots, images of the looters’ continued rampage eventually displaced the fact that an unarmed man was shot to death.’ Rankine asks, “Why don’t you (write)?” Then she goes on to ponder the question.

Arguably, there is no simultaneity between the English sky and the body being ordered to rest in peace. This difference, which has to do with “the war (the black body’s) presence has occasioned,” to quote Baldwin, makes all the difference. One could become acquainted with the inflammation that existed around Duggan’s body and it would be uncomfortable. Grief comes out of relationships to subjects over time and not to any subject in theory, you tell the English sky, to give him an out. The distance between you and him is thrown into relief: bodies moving through the same life differently. With your eyes wide open you consider what this man and you, two middle-aged artists, in a house worth more than a million pounds, share with Duggan. Mark Duggan, you are part of the misery. Apparently your new friend won’t write about Mark Duggan or the London riots; still you continue searching his face because there is something to find, an answer to question.

Claudia Rankine largely talks about the experience about blacks in America. But you know you can see the Dalits of India there. And the oppressed of everywhere there.

You are in the dark, in the car, watching the black-tarred street being swallowed by speed; he tells you his dean is making him hire a person of color when there are so many great writers out there.

You think maybe this is an experiment and you are being tested or retroactively insulted or you have done something that communicates this is an okay conversation to be having.

Why do you feel comfortable saying this to me? You wish the light would turn red or a police siren would go off so you could slam on the brakes, slam into the car ahead of you, fly forward so quickly both your faces would suddenly be exposed to the wind.

As usual you drive straight through the moment with the expected backing off of what was previously said. It is not only that confrontation is headache-producing; it is also that you have a destination that doesn’t include acting like this moment isn’t inhabitable, hasn’t happened before, and the before isn’t part of the now as the night darkens and the time shortens between where we are and where we are going.

How many times have you, in India, faced the question, “Will you choose to be treated by a doctor who got through quota?” But how many times have you faced the question, “Will you find out if the richest doctor running the heppest hospital bought his medical seat with money or privilege?”

A woman you do not know wants to join you for lunch. You are visiting her campus. In the café you both order the Caesar salad. This overlap is not the beginning of anything because she immediately points out that she, her father, her grandfather, and you, all attended the same college. She wanted her son to go there as well, but because of affirmative action or minority something—she is not sure what they are calling it these days and weren’t they supposed to get rid of it?—her son wasn’t accepted. You are not sure if you are meant to apologize for this failure of your alma mater’s legacy program; instead you ask where he ended up. The prestigious school she mentions doesn’t seem to assuage her irritation. This exchange, in effect, ends your lunch. The salads arrive.

How often have you heard someone lament, “I/my son did not get the opportunities we deserved because of reservation.” You ask her, where is she/her son now. In US or UK or Australia or somewhere where he is a big shot. You are never surprised. And you ask the same question to someone who did not get opportunities despite reservation. In a slum. Cleaning vessels. Or wiping tables.

You do not expect them to make it past odds.

The new therapist specializes in trauma counseling. You have only ever spoken on the phone. Her house has a side gate that leads to a back entrance she uses for patients. You walk down a path bordered on both sides with deer grass and rosemary to the gate, which turns out to be locked.

At the front door the bell is a small round disc that you press firmly. When the door finally opens, the woman standing there yells, at the top of her lungs, Get away from my house! What are you doing in my yard?

It’s as if a wounded Doberman pinscher or a German shepherd has gained the power of speech.

And though you back up a few steps, you manage to tell her you have an appointment. You have an appointment? she spits back. Then she pauses. Everything pauses. Oh, she says, followed by, oh, yes, that’s right. I am sorry.

I am so sorry, so, so sorry.

Claudia Rankine explores the conflict between the historical self and the real self that makes you understand your own inconsistencies and social failings.

A friend argues that Americans battle between the “historical self” and the “self self.” By this she means you mostly interact as friends with mutual interest and, for the most part, compatible personalities; however, sometimes your historical selves, her white self and your black self, or your white self and her black self, arrive with the full force of your American positioning. Then you are standing face-to-face in seconds that wipe the affable smiles right from your mouths. What did you say? Instantaneously your attachment seems fragile, tenuous, subject to any transgression of your historical self. And though your joined personal histories are supposed to save you from misunderstandings, they usually cause you to understand all too well what is meant.

As you interact with your brethren in your village, you constantly come in contact with this conflict. You are at a loss to explain how a person, who is so nice, so helpful, so hospitable, so unselfish, so generous when interacting with you, can be so unmindful of the concerns of the lower castes. You see how a Dalit is denied entry into their houses that so welcomed you. You see how the language changes so swiftly from respectful to demeaning, when addressing them. You see how they assert, “whatever you do for them, they are like this only.”

You are conditioned to look at the other with suspicion.

The man at the cash register wants to know if you think your card will work. If this is his routine, he didn’t use it on the friend who went before you. As she picks up her bag, she looks to see what you will say. She says nothing. You want her to say something—both as witness and as a friend. She is not you; her silence says so. Because you are watching all this take place even as you participate in it, you say nothing as well. Come over here with me, your eyes say. Why on earth would she? The man behind the register returns your card and places the sandwich and Pellegrino in a bag, which you take from the counter. What is wrong with you? This question gets stuck in your dreams.

Whenever there is a natural calamity, you call nature a great leveler. Really? Claudia writes in the wake of Hurricane Katrina:

And so many of the people in the arena here, you know, she said, were underprivileged anyway, so this is working very well for them.

You simply get chills every time you see these poor individuals, so many of these people almost all of them that we see, are so poor, someone else said, and they are so black.

Have you seen their faces?

[…]

He said, I don’t know what the water wanted. It wanted to show you no one would come.

He said, I don’t know what the water wanted. As if then and now were not the same moment.

He said, I don’t know what the water wanted.

Call out to them.

I don’t see them.

Call out anyway.

Did you see their faces?

In the few places, where Rankine slips into the first person, she still sews the second person into the first person and the third person, with the sheer power of her narrative. You feel the pain of being singled out.

My brothers are notorious. They have not been to prison. They have been imprisoned. The prison is not a place you enter. It is no place. My brothers are notorious. They do regular things, like wait. On my birthday they say my name. They will never forget that we are named. What is that memory?

The days of our childhood together were steep steps into a collapsing mind. It looked like we rescued ourselves, were rescued. Then there are these days, each day of our adult lives. They will never forget our way through, these brothers, each brother, my brother, dear brother, my dearest brothers, dear heart—

Your hearts are broken. This is not a secret though there are secrets. And as yet I do not understand how my own sorrow has turned into my brothers’ hearts. The hearts of my brothers are broken. If I knew another way to be, I would call up a brother, I would hear myself saying, my brother, dear brother, my dearest brothers, dear heart—

On the tip of a tongue one note following another is another path, another dawn where the pink sky is the bloodshot of struck, of sleepless, of sorry, of senseless, shush. Those years of and before me and my brothers, the years of passage, plantation, migration, of Jim Crow segregation, of poverty, inner cities, profiling, of one in three, two jobs, boy, hey boy, each a felony, accumulate into the hours inside our lives where we are all caught hanging, the rope inside us, the tree inside us, its roots our limbs, a throat sliced through and when we open our mouth to speak, blossoms, o blossoms, no place coming out, brother, dear brother, that kind of blue. The sky is the silence of brothers all the days leading up to my call.

If I called I’d say good-bye before I broke the good-bye. I say good-bye before anyone can hang up. Don’t hang up. My brother hangs up though he is there. I keep talking. The talk keeps him there. The sky is blue, kind of blue. The day is hot. Is it cold? Are you cold? It does get cool. Is it cool? Are you cool?

My brother is completed by sky. The sky is his silence. Eventually, he says, it is raining. It is raining down. It was raining. It stopped raining. It is raining down. He won’t hang up. He’s there, he’s there but he’s hung up though he is there. Good-bye, I say. I break the good-bye. I say good-bye before anyone can hang up, don’t hang up. Wait with me. Wait with me though the waiting might be the call of good-byes.

When the system suspects you every time you do nothing, when the police stop you for doing the regular things, when you are made to explain why you talk when you have done nothing, you know you fit a certain description. Claudia’s hysteric language drives you into a frenzy in this stanza.

I knew whatever was in front of me was happening and then the police vehicle came to a screeching halt in front of me like they were setting up a blockade. Everywhere were flashes, a siren sounding and a stretched-out roar. Get on the ground. Get on the ground now. Then I just knew.

And you are not the guy and still you fit the description because there is only one guy who is always the guy fitting the description.

I left my client’s house knowing I would be pulled over. I knew. I just knew. I opened my briefcase on the passenger seat, just so they could see.

Yes officer rolled around on my tongue, which grew out of a bell that could never ring because its emergency was a tolling I was meant to swallow.

In a landscape drawn from an ocean bed, you can’t drive yourself sane—so angry you are crying. You can’t drive yourself sane. This motion wears a guy out. Our motion is wearing you out and still you are not that guy.

Then flashes, a siren, a stretched-out roar—and you are not the guy and still you fit the description because there is only one guy who is always the guy fitting the description.

Get on the ground. Get on the ground now. I must have been speeding. No, you weren’t speeding. I wasn’t speeding? You didn’t do anything wrong. Then why are you pulling me over? Why am I pulled over? Put your hands where they can be seen. Put your hands in the air. Put your hands up.

Then you are stretched out on the hood. Then cuffed. Get on the ground now.

Each time it begins in the same way, it doesn’t begin the same way, each time it begins it’s the same. Flashes, a siren, the stretched-out roar—

Maybe because home was a hood the officer could not afford, not that a reason was needed, I was pulled out of my vehicle a block from my door, handcuffed and pushed into the police vehicle’s backseat, the officer’s knee pressing into my collarbone, the officer’s warm breath vacating a face creased into the smile of its own private joke.

Each time it begins in the same way, it doesn’t begin the same way, each time it begins it’s the same.

Go ahead hit me motherfucker fled my lips and the officer did not need to hit me, the officer did not need anything from me except the look on my face on the drive across town. You can’t drive yourself sane. You are not insane. Our motion is wearing you out. You are not the guy.

This is what it looks like. You know this is wrong. This is not what it looks like. You need to be quiet. This is wrong. You need to close your mouth now. This is what it looks like. Why are you talking if you haven’t done anything wrong?

And you are not the guy and still you fit the description because there is only one guy who is always the guy fitting the description.

In a landscape drawn from an ocean bed, you can’t drive yourself sane—so angry you can’t drive yourself sane.

The charge the officer decided on was exhibition of speed. I was told, after the fingerprinting, to stand naked. I stood naked. It was only then I was instructed to dress, to leave, to walk all those miles back home.

And still you are not the guy and still you fit the description because there is only one guy who is always the guy fitting the description.

When you are so lost, and so isolated, how do you feel part of a larger society? How do you make the society feel you are part of it? How do you become a Citizen? These are also the questions that the poet grapples with.

Just this morning another, What did he say?

Come on, get back in the car. Your partner wants to face off with a mouth and who knows what handheld objects the other vehicle carries.

Trayvon Martin’s name sounds from the car radio a dozen times each half hour. You pull your love back into the seat because though no one seems to be chasing you, the justice system has other plans.

Yes, and this is how you are a citizen: Come on. Let it go. Move on.

Despite the air-conditioning you pull the button back and the window slides down into its door-sleeve. A breeze touches your cheek. As something should.

Claudia Rankine manages to slam you and hem you into a black body set against the whitest background. You feel the pain. You feel the indifference. You feel the suspicion. You feel the discrimination. You feel history. And you feel the present. You feel no escape.

you’re not sick, not crazy,

not angry, not sad—

It’s just this, you’re injured.

—-

And where is the safest place when that place

must be someplace other than in the body?

You feel the urge to reproduce her entire book in this essay. You have to only say so little when her book says so much. But you have to stop somewhere.

I can hear the even breathing that creates passages to dreams. And yes, I want to interrupt to tell him her us you me I don’t know how to end what doesn’t have an ending.

Tell me a story, he says, wrapping his arms around me.

Yesterday, I begin, I was waiting in the car for time to pass. A woman pulled in and started to park her car facing mine. Our eyes met and what passed passed as quickly as the look away. She backed up and parked on the other side of the lot. I could have followed her to worry my question but I had to go, I was expected on court, I grabbed my racket.

The sunrise is slow and cloudy, dragging the light in, but barely.

Did you win? he asks.

It wasn’t a match, I say. It was a lesson.

What is poetry? What is the purpose of poetry? Does poetry need a purpose? Shorn of all rhyme, rhythm and even form, what differentiates poetry from prose? You are left with these and more questions. You may not yet have the right answers but you know all the answers you knew earlier are wrong. You know you have not even started asking all the right questions.

Claudia Rankine quotes Dostoevsky and James Baldwin.

“The purpose of art,” James Baldwin wrote, “is to lay bare the questions hidden by the answers.” He might have been channeling Dostoyevsky’s statement that “we have all the answers. It is the questions we do not know.”

Claudia Rankine is not the first person to write poetry in the form of prose. Nor is she the first person to employ the second person pronoun so extensively. Nor is she the first to use poetry to drive home political points. But she is, clearly, a masterful exponent of all these.