“Devadasis: Beyond Conventional Constructs” by B.C. Anish Krishnan Nayar published in Tamizhini on September 13, 2018 was an exercise in revisionism and mudslinging. The author tries to flatten a complex history into a whitewashed simple portrait of devadasis as holding a place of pride in Tamil society and even as vanguards of Hindu faith with deep scriptural knowledge that was a counterweight to the onslaught of evangelical missionaries. Along side such revisionism the author characterizes the efforts to abolish the devadasi practices as misguided colonialism and the result of evangelical propaganda.

What can we say of an article on devadasis that refers to the reform movements and does not even mention the name Dr.S. Muthulakshmi Reddy or any academic literature? This rebuttal to that simplistic portrait will use considerable material from an earlier blog published on my personal blog on the same topic. However, I’ll add a few more perspectives that I’ve since gained and add comments as to why I consider the column by Mr. Nayar as lacking in substance.

Nityasumangali : Virali as precursor to Devadasis and Devadasi as eternally auspicious

Saskia Kersenboom-Story’s “Nityasumangali: Devadasi Tradition in South India” explores the antecedents of the devadasi outside the confines of typical historical inquiries. She states clearly at the outset that her’s is not a “study of the fact of the devadasi tradition, but of its meaning and the mode of production of that meaning” (emphasis by the author in original text).

Kersenboom locates the devadasi tradition in the Sangam era (circa 3rd century Common Era) in the bardic traditions where the female bard is referred to as virali. “The dancer-cum-singer Matavi of the Silappattikaram exemplifies this change of virali-patini into the courtesan ganika, who is well-known from Sanskrit literature. At the same time Matavi retains strong bardic, Tamil traits: her first alliance is to the king, and after her debut in his court she receives gold and a garland in truly bardic fashion”. The second antecedent that Kersenboom traces for Devadasi- Nityasumangali is within the broader bardic culture.

The devadasi tradition is chiefly associated with three eras that the author roughly divides as follows:

- Rule of the Pallavas and Pandas (550-850 A.D.)

- Rule of the Cholas (850-1279 A.D.)

- Vijayanagara Empire (1336-1565 A.D.)

(Note : I’ve used the notation of A.D. as used by the author. Wherever authors have used it I’d stick to it and in other places I’ll gladly use the now politically correct C.E.)

“By the time of medieval literature”, like Paripatal ( circa 350-600 C.E.), virali has “changed from the bardic professional songstress, dancer and musician, into a mere messenger between the hero and heroine. They maintain the “tiniest possible link with religion”. As the 8th century rolls in “more subdued expressions of worship as well as offerings of a more artistic character may have been added”. “This combination of ritual and artistic service of woman to a god in a temple is the most generally accepted image of the devadasi. This character emerges first in the later centuries of the Pallava-Pandya rule”.

The Saiva saint Manikkavacakar is recognized as the point of inflection in “reformulation of bardic performance into devadasi-nityasumangali” construct. His significance lies “in the fact that his work seems to represent a completion of the synthesis of the bardic Tamil culture and Brahmanic tradition of ritual and philosophic thought. The circle of transformation appears to have reached fruition: the ‘bardic’ king was supported by male and female bards who sustained his Fame and Honor, his very life-essence, and who dwelt with great sensitivity on the subject- matter of love”.

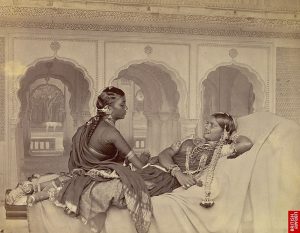

It is during the Vijayanagar empire, when it was the most important rampart in the defense of a Hindu empire against the Muslim incursion, that the nityasumangali tradition gets entrenched. It is during this period that documented history of a place of pride for devadasis (note, this use of the term devadasis across the era is rather inaccurate as a later discussion will show). Devadasis, unlike others, could chew betel in front of the king. During this era we come across visnudasis and rajadasis, the temple slave and the court slave.

During the Vijayanagar empire period the idea of eternally auspicious took root as the non- conjugal lifestyle of the devadasis conferred upon them the special privilege that they’ll never lose their auspiciousness and as such they were invested, ritually, with the power to purify the king.

The collapse of the Vijayanagar empire saw the shift of the Hindu empire further into the South in what is today Tamil Nadu. Tanjore became the chief locus of the Hindu empire. With that shift other ominous changes took place. Chiefly, the devadasi was beginning to be sidelined from temple rituals by a Brahminical order.

For a clear head historical analysis of the story of devadasis we need to move on to Davesh Sonjie’s admirably scholarly “Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory, and Modernity in South India”.

Who Were the Devadasis?

“The terms devadasi is rarely encountered in Indian literary or inscriptional material prior to the twentieth century”. “It is also significant the the temple focus on devadasis arises only once moral deliberations on these communities come to occupy central stage in twentieth century Madras”.

The first myth that Soneji dispels with is the narrative of devadasis as a singular category and as a group of women who held a place of pride in the society due to being associated with temples as ‘slave of god’. The women had a ‘contentious status’ owing to their non-conjugal sexual lifestyle and were alternately referred to as ‘dancing woman, concubine and court servant’.

Soneji equates the pottukattuthal ceremony with kattikalyanam (dagger or sword marriage) and notes that many dancing women were betrothed to a God, if at all they were, in home ceremonies and not in temples. The Maratha records did not give any religious symbolism to this ceremony. “Dedication rituals so fetishized by scholarship on devadasis has less to do with theological symbolism than it does with economic investments”. Time and again Soneji deglamorizes their lives as “quasi-matrilineal” and not ‘matrilineal’ because many lived as concubines and their much valorized economic independence was just a fairy tale. Annam, a a dasi in 1842 had her pottu tied at the age of ten and she, according to records, was entitled to “one kalam paddy every month and one-and-a-half handfuls of cooked rice a day”. Thus the pottukattuthal ceremony was a ‘transaction that secured a girl’s commitment to local economies of land and guaranteed her sexual and aesthetic labor’.

“Slavery was a major part of the economy of the Tanjore Maratha kingdom”. “Young girls who were orphaned or destitute were often bought by the court in order to have a pottu tied and then given to a courtesan household …or simply lived with the concubines in seraglios”. This adoption of orphans by devadasis became a key legal issue in the colonial rule.

‘Nautch’ and Amy Carmichael

The other myth that Soneji destroys is attributing the demise of the ‘temple’ devadasi system to the rise of the “nautch” performances that in turn stigmatized a glorious tradition. South India, Soneji establishes, had a vibrant courtesan culture that included both Hindu and Muslim women. The courtesans were, contrary to myths, the mainstay of dance and aesthetics. Most of the courtesans were in no way part of the temples wedded dasis.

Having established the prevalence of a courtesan culture Soneji immediately turns to ‘European engagements’. “Representations of devadasis in this period emerge out of alliances between Christian evangelicalism, colonial anthropology and imperial medicine, all of which were directed toward the moral reformation of women from these communities”. Part of the animosity of many towards evangelical influence on devadasi abolition is premised on a utopian retelling of their lives. As we saw briefly, it was anything but idyllic. The system, in fact, was crying out for reform. Sonjie, specifically mentions Amy Carmichael (1867-1951) and her reform efforts. Carmichael went on to form rehabilitation centers for children of devadasis. It’s easier to malign Christian missionaries than to at least nominally recognize the services they provided in the social vacuum that Hinduism had left many in.

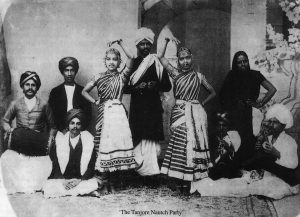

Nautch Dancer

The dance repertoire of the courtesans were very unlike what revisionist historians of Bharatanatyam would have us believe. The courtesans did not only dance to erotic verses but also to compositions that would be laughed today as stunts. Chennai Nellaiyappa Nattuvanar, grandson of the Tanjore Quartet, composed a performance where the dancer would tied vegetables to their bodies and would slice them off while dancing. The ‘nautch’ performances included both Hindu and Muslim girls.

To be sure colonial era writings and missionary records were written to portray the “civilization depravity of the ‘oft-conquered people’ of India”. No missionary work, however noble, was divorced from proselytization. Too often missionaries impressed upon their beneficiaries that their plight was the result of not just their socioeconomic circumstances but because of Hindu theology. Now, to be fair to the missionaries, there were times when that was true too. Often the conversions, to state a fact, were not the panacea that they were promised to be but that’s a whole another Pandora’s box beyond the current purview.

The Legal Code and Devadasis as Prostitutes

Introduction of modern jurisprudence and the codification of laws to govern an ancient country that had become a melting pot of civilizations became the foremost challenge of the colonial government from the East India Company days. Few realize how much Brahminical Hinduism informed the codification of those laws from the 18th century. Brahminism, long relegated to the shadows during Islamic rule, found a resurgence to prominence and position of eminence during Colonial rule. While on the one hand Colonial and evangelical writings were harsh about India’s civilization its opposite also was true. Indology, as a study, established during that era has provided yeoman service to resurrecting India’s glorious past.

“Victorian notions of sanitary reform and social hygiene were also influenced by the growing importance of eugenics”. Devadasis were compelled to register and be tested for venereal diseases following the Contagious Diseases Act. Exemptions, however, were given to temple bound devadasis. A British Medical Journal on the study of STDs (Sexually Transmitted Diseases) in India (independently sourced by me) corroborates Sonjie’s data that curbing STDs was a strategic importance for the British army because the soldiers had been “encouraged to have non-committal sexual relationships with natives”. Guess which class of women were ripe for non-conjugal sexual liaisons and thus liable for being infected by a disease that arrived in India, probably, through the Portuguese. Soneji cites an important work that details how British feminists who used the image of Indian women as ‘white women’s burden’ and connected it to imperialism to create a political platform for their own feminist movement back home.

An Indian can bristle at the notion that a colonial regime had to introduce sanitary reforms but let’s not forget that sanitary reform was equally the Mahatma’s key agenda. Whenever Gandhi entered a village he was known to inquire if the village had toilet facilities and if the answer was ‘no’ he’d start instructing them to construct a latrine. A key challenge even today in India is the preponderance of open air defecation. Introduction of modern medicine created its own profound frictions with an ancient society.

One of the cornerstones of modern jurisprudence is property rights and an important feature of property rights is inheritance. On framing laws Colonial officials, time and again, more than is realized, yielded to local customs. Chandra Mallampalli’s “Christians and public life in colonial South India, 1863-1937” recounts a legal odyssey in establishing inheritance rights for converted Christians. It is unbelievable how much the colonial governments, especially after 1857, were reluctant to interfere in local customs. This backdrop is important in understanding what unfolded with regards to Devadasis.

Though Soneji is familiar with Lucinda Ramberg’s “Given to the Goddess, South Indian Devadasis and the Sexuality of Religion” he did not delve deeper into the legal background.

“Precolonial patterns of matrilineality among the Nayars of Kerala were undermined by court decisions that favored male inheritance and re-framed Nayar sambandham 7 alliances as concubinage rather than marriage. Through readings of the colonial legal archive of the Bombay courts, Rachel Sturman describes the codification of Brahmanical marital practices in Hindu family law as the norm for all communities. Mytheli Sreenivas (2008) argues on the basis of court decisions about disputes in Tamil Zamindari households over property and inheritance that legal institutions distinguished concubines from wives. This distinction was not made in terms of sexual relations, reproductive issue, or affective proximities, but by recourse to the form of the marriage ceremony, the place of the woman’s residence, and her caste identity. Sons of wives were designated legitimate heirs to Zamindari estate property; sons of concubines were not. Women’s relationships to property, as well as to the state, were determined by their socio-sexual status. As Sreenivas points out, the courts were not just adjudicating the question of women’s status, they were at the same time defining the possible meanings of, and criteria for, the positions of wife, widow, and concubine. (I’ve removed the source references cited by Lucinda Ramberg in academic practice within parentheses to avoid confusion and for readability. This paragraph is from ebook edition pages 151-152)

In short, colonial efforts to define what might constitute legitimate marriage had several effects. The Brahmanical patrilineal descent became the legal norm for all alliances between men and women. The normalization of this form served to establish a clearer distinction between marriage as a form in which women (and the sexual access to them that marriage confers) are given, and slavery as a form in which women (and sexual access to them) are sold. The question of female sexual purity and its ties to the status of the nation were also central to the production of the wife and the prostitute as mutually exclusive categories of sexual person-hood and status. Modern conceptions of sexual person-hood and the new science of sexuality combined with the nationalist quest for sexual respectability to establish the wife as the body of honor for the new nation.” (Page152-154)

The colonial government codified laws that incorporated Hindu caste traditions and the devadasi community posed a challenge to easy categorization. The legal system categorized devadasis as a ‘caste of professional prostitutes’. It is here that one should pause and ask how did the characterization happen? Was it the malicious propaganda of evangelists or racist colonial officials who did not understand a unique customs that was unheard of in their social outlook? Soneji, writing in 21st century, refers to Devadasi lifestyle as ‘non-conjugal sexual lifestyle’.

Such vocabulary did not exist until recent times. As briefly mentioned above even native records referred to devadasis with vernacular equivalents of prostitute. But that was not all.

Devadasis and Native Literature

Surveying native literature between 1850-1950 Soneji establishes that it is not just missionary literature that maligned the devadasis. Anyone who has a little reading of the uphill struggles of reform movements would consider it laughable that an ancient society which had hitherto, according to popular belief, held devadasis in high esteem just switched its vocabulary to calling them as whores because foreign evangelists called them so. It is useful to again recall Sonjie’s assertion that devadasis always had a position of ambiguity.

Racavetikavi, a ‘resident of Tiruttani’, published in 1864 (3 years before Amy Carmichael was born), “Poem on the transformation in the nature of the courtesan”. The poem depicts courtesans as vesya and gives extremely pornographic descriptions of not just sexual act but of venereal disease too. “Full of lust he feels the urge again…On seeing her, he pulls back the foreskin, and notices a small leakage of blood and urine”. Another work, Varakanta, published by Raja M. Bhujanga Rau Bahadur, in 1904 also portrays devadasis as temptresses who lure and defraud men. Another text published in 1943 refers to devadasis as ‘Vesi muntaikal’ (ேவ#µ%ைடகll). Sonjie concludes, “representations of devadasi-courtesans in vernacular literature” gives us an idea of their “ambiguous social and moral status”. These texts also go a long way in establishing the “trope of the lascivious and money hungry courtesan”. It is complete nonsense to attribute attitudes to devadasis entirely to colonial and evangelical literature. Rather, native and colonial literature converged in late 19th century.

The Abolition Movement. Devadasis and ‘Respectable Citizenship’

Notably, much before the anti-nautch movement began in Chennai the fiefdom of Pudukottai, in 1878, had initiated it under the guidance of the divan A. Sashiah Sastri. There’s no evidence that Sastri was enthralled by evangelist literature. He did it to protect a young king from squandering his wealth in licentiousness.

What really under girded the anti-nautch movement? Emerging ideas of nationalism that posed the questions of what kind of a nation will India be, what will be its social mores, what reforms were needed in practices that no nation entering the modern era could afford to retain and more. Reforms for women and lower caste members drew the most attention. As regards women, their education, rights, widow remarriage, raising the age of marriage occupied the forefront of reformist agenda. Did these ideas sprout from modern education and awareness of modern world and especially an understanding of biology due to modern medicine? Absolutely yes. But that does not mean that India’s reformers were pawns to colonial and evangelical prejudices. Such a view does gross injustice to the many who valiantly did everything they could to make an Independent India a better place for all.

Soneji identifies Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddy, Muvalur Ramamirtham and Yamini Purnatilakam as the trio that waged a battle against devadasi system in South India. What connected the three women? Gandhi and emerging nationalism.

A landmark event that triggered the anti-nautch movement was child trafficking. The marital-rape death of Phulmoni Das, a 10 year old girl, became the reason for the promulgation of ‘Age of Consent’ bill in 1891. Bala Gangadhar Tilak, amongst many, fought the bill tooth and nail as interfering with Hindu customs. Tilak went to the extent of arguing in favor of the husband. Around the same time was the Rukhmabai case (Soneji does not mention this) where Rukhmabai, a child bride, had to resort to extended legal means to not live with her husband. She became a doctor.

Child prostitution was a reality. The many devadasis that Soneji interviews or cites became devadasis when they were, literally, children, including Muvalur Ramamirtham. Muttukannammal, interviewed by Soneji, was dedicated at a temple at the age of seven. Anyone who portrays devadasi system as some hallowed paradise torn asunder by evangelical prejudice is ignorant of history or bigoted.

Muthulakshmi Reddy’s anti-nautch effort were “inextricably linked to Congress politics and Theosophical society” and “emergent notions of eugenic health”. Annie Besant’s Theosophical society created a schism in South Indian politics with its extravagantly enthusiastic adoption of Brahminical Hinduism as the ideal end state for an independent India. The after effects of that schism continues to ricochet till today in Tamil Nadu.

Soneji details how a section of devadasis themselves opposed Reddy’s movement. A significant figure was Bangalore Nagarathnammal. Interestingly not one of those who opposed Reddy had been dedicated at a temple. This underscores how ‘devadasis’ is a loosely used terms. In fact the trope of devadasis as beholden to temples was assiduously promoted during this period of conflict to escape moral approbation. Later when the arts were appropriated by the Brahmins and history was re-fashioned this myth became so well entrenched that it has become an article of faith. But, facts, as Soneji marshals, are stubborn.

Soneji, citing several researchers, establishes how “health of the nation was liked to the goal of swaraj”. “Politics of respectability was a cornerstone of Congress nationalism” and that was invariably patriarchal in outlook. Addressing a meeting in Rajahmundry in 1921, quoted by Soneji (and I’ve corroborated it in D.G. Tendulkar’s biography of Gandhi) Gandhi calls for women to ensure that there is “no single dancing girl” in the region. When Muvalur Ramamirtham and another dash offer jewels to Gandhi he refuses to accept them until they led “a respectable married life”. “He asked that they wear and display talis or mangalsutras”. A man wrote to Gandhi about the necessity for “moral elevation” of devadasis and Dalits. Note, the twinning of two very different people. All three women reformers saw, like Gandhi did, that marriage was the respectable institution for women.

Myths and Realities of Devadasis

As regards the fabled property rights of devadasis Soneji is categorical in characterizing it as “loose matriliny” in several places and he highlights some families where inheritance continued through male and female offspring. Likewise it is an oversold myth that Devadasis were well learned. Even researchers like Paxton, cited by Ebeling, embellish that. But material provided by Soneji says otherwise. A Telugu Brahmin wrote a treatise in Telugu, explaining dance postures, so that he “could facilitate learning for the vesya stris” without having to study abstruse Sanskrit texts. Only highly accomplished courtesans were taught texts like Gita Govind by “Brahmin connoisseurs with whom they often shared intimate relationships”.

The reforms did disenfranchise the devadasis socially and economically. The collapse of the Maratha regime in the 19th century and later the abolition of Zamindari system in independent India essentially sealed the fate of devadasis. The human cost of the disenfranchisement is real but so was the cost of the system.

It is often forgotten that devadasis or courtesans were never really free or independent as the modern women today. Courtesans in the Maratha court were severely restricted regarding where they were allowed to dance and gain revenue. A dasi dedicated to Brahadisvara temple was fined for performing at a private event.

After witnessing a performance by courtesans (kalavantula women) where very explicit and erotic gestures were employed and middle class morality was mocked Soneji cautions us from reading too much into that as independence. “I am conscious of the fact that Kalavantula women were themselves dependent upon the world of men in ways that implicated them in larger, systemic forms of discrimination and potential exploitation”. This complexity is often lost sight of in simplistic romanticized notions of sexual independence and exaggerated ideas of what that sexual independence could really be.

Photo Courtesy : Hooper

A historian, even a lay and itinerant student like me, should look at diverse sources and judge if a point of view can be sustained by not just other authors and other books but books on tangentially related topics.

Sonjie’s accent on emerging nationalism, the debate of ‘respectable citizenship’ and Gandhi in the abolition movement is buttressed by Mrinalini Sinha’s “Specters of Mother India: The Global Restructuring of an Empire”. Gandhi had called Katherine Mayo’s ‘Mother India’ a drain inspector’s report. But the book set off a nationalist reaction that wanted to respond by modernizing its society and an important fallout was the ‘Sarada Act’ that abolished child marriage.

Sinha argues that the “focus on modernizing of marriage and family life” was the result of a “convergence in the early twentieth century go particularly dense economic and social forces”. Indian women and women’s organizations, just as in devadasi abolition, played a key role. It is beyond uncharitable to attribute devadasi abolition to anyone other than India’s own wonderful women. Colonial outlook, evangelist literature, reports of drain inspectors were but marginal factors as a nation willed itself into modernity and reformed ancient, very ancient, customs. This is why even Soneji dwells more on domestic causes than on anything else.

Did Victorian Morality Change Indian Sexual Mores?

As regards the much emphasized sexual freedom of devadasis we’ve already seen how that could be argued as more in service of patriarchy than a true freedom. Corollary to that is an oft repeated trope about Abrahamic faiths and particularly the importation of Victorian morality corrupting a culture that treated sex as healthy pursuit even to the point of being hedonist about it in literature and temple sculptures. Amartya Sen quoted his teacher at Cambridge to say that the “frustrating thing about India is that whatever you can rightly say about India, the opposite is also true”. Yes India is the land of Kamasutra and Ajanta but it is also the land of scriptures that, like every other culture, laid down the most stringent rules for women especially on matters of sex and practically treated them as creatures of wanton lust to be kept on a leash.

Arti Dhanda’s “Woman as fire, woman as sage: Sexual ideology in the Mahabharata”. “Mothers in the Mahabharata are frequently cast as all-wise, all capable characters”. Other women are linked to sin, snake, sharpness of a razor and poison. Sexologist Sudhir Kakar, strangely he’s not cited by Dhanda, labels this the ‘mother-whore’ dichotomy in Indian attitude towards women and their sexuality. It’d be abjectly silly to think that Gandhi’s quest to become sexless, a near fatal obsession for him till his last day, had anything to do with Victorian or evangelical morality. Indians need no lesson in misogyny or suspicion of sex.

The devadasi system abolition needs to be understand against a complex tapestry as outlined above. In reality economic forces, emergent notions of nationalism, role of women in society, protection of children, introduction of modern law and medicine, all contributed to the demise of the society. This is not to mean that colonial regime, its literature and governance and evangelicals had no role in it but they were, in reality, not the driving force or even the spark. It is ironical that I, of all people, have to argue forcefully in giving Indians their due for a major reform. That is because many, these days, are ill-informed and based on myths blame the reforms for a supposedly idyllic system that was destroyed. This view is akin to Margaret Mitchell bemoaning the loss of the South’s traditions as “gone with the wind”.

The seminal influences on Indian culture and social mores could be more attributed to the advent of modern education and the expanding frontiers of science. Of course, on both of those counts the contributions of the colonial regime and evangelists was significant.

Revisionism and Mudslinging

Mr. Nayar fires salvo after salvo of declarations with little supporting material. He says, “Now there are arguments that the abolition of the devadasi system itself was an ignorant, knee jerk reaction of a patriarchal society that wanted to boost its progressive credentials.” Pray, what are those arguments? As outlined above the abolition of devadasi practice was far from knee jerk and it ran into the buzz-saw of atavist tradition upholders and had risen out of true concern about what the practice had not only become and the reform movement was the result of a confluence of events shaping the country then.

We’re told, “There are a number of feminist scholars who now argue that the Devadasi system had provided the women of yester-centuries with the freedom to pursue arts and property rights when compared to other women of that age who were shackled to domestic duties.” Sonejie and Ramberg more than demolish this myth as recounted earlier.

Mr. Nayar tells us that “the assumption, that a woman is doomed or saved by men ignoring the role of woman and the validity of her choice, is severely criticized in contemporary feminist discourse.” But then the reform movement was led by women and even its opponents had women from the devadasi community. Men, to be sure, were not entirely divorced from the movement but were marginal in this reform.

The memories of the valiant struggle of a woman like Dr. S. Muthulakshmi Reddy is besmirched by Mr. Nayar’s contention, “ironically, women who took an active part in such “reformist” movement are now being considered as mere pawns who chose the dominant ideology over their individual agency.” Both Dr. Reddy, one of the chief leaders of the abolition movement, along with Muvalur Ramamirtham Ammal and others, was anything but a pawn in the hands of anyone. The ranks of the opponents included the likes of Bangalore Nagaratnam Ammal, who is credited with almost single-handedly creating the cult of Thyagaraja worship. She would not hesitate to box the ears of Mr. Nayar for characterising her as a pawn.

Surprisingly Mr. Nayar finds Amy Carmichael as a source for reliable history when he approvingly quotes her to establish that “most of the devadasis had a very strong footing in religious texts.” This is wrong on two counts. While devadasis, compared to other women, were indeed literate but the extant of literacy and the number of literate dasis is vastly exaggerated in that statement by Mr. Nayar. Second, devadasis have never produced any body of work tat reflects either literacy in general or their grounding in scriptures. Note that dasis repeatedly engaged Brahmins to write javelis and padams for them. This then puts to doubt this oft repeated exaggeration of the courtesan being highly literate.

In light of the above argument it is beyond ridiculous to even suggest that the devadasis were rivals that the missionaries had to vanquish to further their proselytization. Mr. Nayar is actually diminishing credit from the Brahmins who were the ideological guardians of Hinduism and repeatedly engaged the missionaries on philosophical debates. I guess he’s trying to curry some progressive credentials as much as he may loathe that term.

The devadasi system died a well deserved natural death amidst a panoply of causes. Any such reform can be second guessed for how it could’ve been done without adversely impacting a community at large. History disappoints us with any example of an upheaval that did not at all crush many in its maw as progress rolled forward. The question however is if reform did not happen how many more would’ve languished.

References

- Devadasi Abolition Act: Success of Reformist Movement or Evangelical Corruption of Indian Values? — https://contrarianworld.blogspot.com/2018/05/devadasi- abolition-act-success-of.html (this article has already incorporated large parts of that blog)

- Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory and Modernity in South India – Davesh Soneji, University of Chicago Press

- Given to the Goddess, South Indian Devadasis and the Sexuality of Religion – Lucinda Ramberg, Duke University Press

- Nityasumangali: Devadasi Tradition in South Asia

- Devadasis: Beyond Conventional Constructs – B.C. Anish Krishnan Nayar https://tamizhini.in/2018/09/13/devadasis-beyond-conventional-constructs-bcak-nayar/