Jurek Becker’s “My Father, the Germans and I” is another book that I stumbled across randomly in the library. I picked up the lightweight hardbound book just because I liked the feel of it and the title held some interest to me. I had never heard of the author before. I am so glad that I took this book, a collection of essays, lectures and interviews, edited by his wife Christine Becker, and translated from German by various authors.

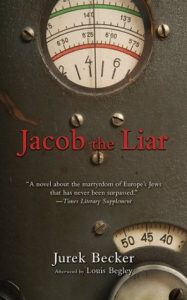

Jurek Becker’s work is important for his views on three crucial aspects: Jews, socialism and literature. He gained renown through his first novel, ‘jakob der lugner’ (Jacob the Liar), about life in a Jewish ghetto. This novel had been made into two films.

Jurek Becker

Jurek Becker was a Jew, who had, as a child, survived the ghettos and concentration camps of Poland. His mother was killed in the concentration camp. His father, or the person who claimed to be his father, survived and found him. His father, quite strangely, chose to settle down in East Germany, at Berlin. Jurek could never quite find out the exact reasons for his choice but he cites some of the reasons given by his father.

So my father proceeded from the premise that if a man feels drawn to no place in particular, he will feel most comfortable staying right where he is.

He alluded to but one of his reasons for staying there, and then only occasionally and indirectly; yet it was enough that I was later able to make sense out of it. He believed that in his old environment, in Poland, Antisemitism did not appear for the first time when the Germans marched in. And the fewer the number of Jews living there, the greater the chance that people would try to make life difficult for them.

Once he said: ‘In the end it is not the Polish anti-Semites who have lost the war.’ He hoped the discrimination against the Jews would be most completely done away with in the place where it had taken on its most horrifying expression. And when he died in 1972, he was happily convinced that he had not been wrong on at least this point. He once said: ‘If Antisemitism did not exist – do you think I would have felt like a Jew for a single second?’

Jurek too did not regret the decision of his father. In his essay, ‘My way of being a Jew’, he writes:

In the area where I grew up, there were no assaults on the group of Jews. Not of the sort I would have noticed, at least, and not of the sort aimed at the Jewishness of people who certainly were something more than just Jews. We all are familiar with the man who cries ‘Antisemitism’ at every mention of his misbehavior. Just as we all are familiar with the government that, when accused of improper conduct, makes ‘anti-socialism’ its excuse. One really has to be careful.

This refusal to use ‘victimization’ as an excuse to justify anything shines through all his essays. He adds:

I never sought the company and companionship of Jews, nor did I avoid it. I discovered whether someone I knew was a Jew or not only by chance, if at all. If someone intentionally drew my attention to this fact, the same question would always run through my mind. Why is he telling me this? I may even have felt somewhat disgusted. For it seemed to me that the person in question expected me to behave differently toward him, upon learning that he was Jew, than I would have done normally.

We see this clannishness and victimization exhibited by many groups across the world, and not just Jews. Jurek Becker doesn’t also stop shy of being critical of Israel’s actions in the middle east.

In his speech, ‘resistance in jakob der lugner’, he dwells on the resistance of Jews during the Nazi regime.

Now about resistance: I’m sure I don’t have to tell you here the extent to which the Jews were persecuted during the last war. The facts are known and for the last thirty-eight years mankind has had to live with these facts. It has done so quite well. Ever since I have been able to think, I have been preoccupied with the question why the resistance against Jewish extermination – I mean the Jewish resistance, the resistance of the victims- was so unbelievably small. This is not the right occasion to analyse the possible reasons. Here I would only like to say a few words about the extent of this resistance.

The whole of Eastern Europe was covered with ghettos. The ghettos were the waiting rooms to the concentration camps where millions of people- whether aware or unaware of it- awaited their extermination. I was put into one of there ghettos as a small child. If I’m not mistaken it was the largest one there was, in Lodz. And now listen: There is only one single case known where Jews pulled together to defend themselves against their persecutors. It was the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising which Heinz Wetzel used as an example in his letter. Here and there there were what perhaps could be called small flareups. But these don’t deserve the name ‘organised resistance’ and, by the way, they never took place in the concentration camps. That is all. In those hundreds of ghettos people awaited their end silently. Perhaps hopeful of some miracle of liberation, perhaps too weak to defend themselves or too afraid, or perhaps too discouraged. Nowhere, except in this one case, was the fist pulled out of the pocket.

Is it appropriate to cite the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising as an example, as if it were at the beginning of a list? I don’t think so. This instance was unprecedented and unique. It was more a big exception than an example. […]

It is in this context that I view the possibility of non-violent resistance against Nazis. Gandhi’s views on Hitler and Jews are generally dismissed as naive, even by sympathizers like Guha. But in the near-complete absence of any form of resistance, I do not think it was out of place for Gandhi to suggest non-violent resistance. His seemingly insensitive tone and words to Jews can be criticized but his suggestion of non-violent resistance itself cannot be dismissed offhand. We do not ever take into account the position of Jews if the Allied powers had not come to their assistance. Could a non-violent movement have succeeded? We do not know. But it had as good a chance as no-resistance or violent resistance.

Jurek Becker goes on to surmise the exaggerated depiction of Jewish resistance in literature.

I ask all of you- after this short and probably unnecessary historical oration- to ask yourselves the question what has become of resistance in the literature of this period. Without exaggerating you can say that in books it has made an astonishing career. Without exaggerating you can say that the literature about this period is really literature about the resistance. The big exception has suddenly become the rule- the unheard-of and unique became an every-day occurrence. The reasons are obvious. It is more pleasing to believe that victims defend themselves; it is more pleasing to believe that injustice has a hard time succeeding; it is more pleasing to believe that the number of resistance fighters was large. With the years this number has continually grown. Just like the number of those who were fascists with the years decrease. Come today to Germany and listen around- you would think that Hitler stood alone in the pasture.

This is what I’m leading up to – how the role of resistance in literature has become inflated, and how this subsequently lessened the feats of those who actually did put up a resistance. They were the big heroes, the big exceptions; the abundance of resistance in books however makes them commonplace. And the others: the unheroic, those who were afraid, who were apathetic, the insignificant, the cowards, thus almost all- they somehow get lost in the books, they hardly exist.

Jurek Becker also throws hints of admission that his own account of the Jewish condition may not be accurate. When asked in an interview, “Tell me, which of your books did your father live to see?” he replied,

Only Jakob der Lunger, which was unfortunate, since he didn’t talk to me for a long time after reading that book. He found it outrageous. His only comment was, ‘You can lie to the stupid Germans about the conditions in the Ghetto, but not to me- I was there!’

As someone who lived in East Germany, he gives a unique perspective of life behind the iron curtain. He has this to say about censorship:

I want to briefly mention another aspect of censorship without which this phenomenon’s description would be incomplete. I have said that only very few books are banned in the GDR, and that is, without a doubt, the truth. But what one really must consider is just how many books never get written in the first place. How many writers take the work off the censor’s plate by inviting censorship into their own heads, that is, by thinking about the difficulties of censorship from the beginning and avoiding them, in short, by becoming opportunists. Of course, I cannot give you numbers- because what does not actually happen cannot be captured by statistics. But I have no doubt that there are many books that do not get written.

It is a commentary not just on censorship but on human psyche and on statistics itself.

But he remained a committed socialist. His criticism of his country was that of an insider wishing to reform the system than a dissenter trying to escape from it. In the end, when he did leave his country, it was for personal/literary reasons than for seeking political asylum. He was aware that he enjoyed special privileges in his country because of his fame in the west. Yet, he resented the reasons for which dissidents were lapped up by the west.

My most recent book Sleepless Days has been banned in the GDR. It is a book by a socialist writer, written out of concern for the development of socialism in the GDR. It has appeared only in the West. Now, when many Western newspapers praise me for the book, it is certainly not out of concern for the development of socialism in the GDR. Rather, as I see it, the opposite is the case. The publicity granted here in the West to some writers who are banned in the East is not at all meant to initiate a discussion of their opinions or to help further their cause. It is often only meant to increase problems for the Eastern governments and to demonstrate to the population in the West how undemocratically things are done in socialist countries. And, incidentally, the books are supposed to sell.

He was not a dogmatic denouncer of censorship either. He endorses Brecht’s call for sensible censorship.

Brecht maintained that all those writings should be censored that practice race-baiting, that glorify violence, propagate war or contain fascist propaganda. That I find okay. And that also means that every other literature should be published and made available to the public. But that is far from being the cases in the GDR.

His depiction of the press freedom in a dictatorial socialist country actually doesn’t seem very different from what we see in our free societies.

I live in a country that has only one single newspaper. To be sure, it has forty or fifty different names. […] Variations in name aside, it is still really only one single newspaper, because it has the same editor-in-chief. And this editor-in-chief is, at the same time, the head of programming for all the radio stations in the country and all the TV stations. On top of that, he executes his office in a very authoritarian and systematic way. What this means is that all these newspapers, journals, magazines and radio and television stations represent only one opinion, namely his, the editor-in-chief’s.

As a corollary to the uniformity and uni-dimensional nature of news and opinions presented by mass media, he feels books play a complementary role.

As an almost inescapable result, books are the only public forum in the GDR where any kind of intellectual controversy is taking place, where disagreements are discussed, where different opinions meet and where everything is not yet organised into Above and Below and Left and Right. There is still curiosity when one reaches for a book, a curiosity that no longer exists when one opens a newspaper and that radio can only inspire when it plays music.

He is scathing in his analysis of the impact of literature in the West. He even ventures to suggest that literature in the west is not resisted because it is harmless. There is truth in it.

Most writers in the West don’t associate themselves with a particular political agenda. On the contrary, it is considered narrow-minded and naive or hopelessly un-modern or even dogmatic to advocate any particular political programme. This kind of detachment when it comes to politics, I dare say, has led to the social ineffectiveness of literature. and this ineffectiveness results in the widespread liberality of writers in the West. In other words, the price writers in so-called Western democracies pay to be able to write, in principle, whatever they want is pretty high in my eyes. The price is that literature has no effect on anything and no impact except for producing a few reviews now and then and sometimes stirring things up among insiders. Why in God’s name should a society treat its literature restrictively when this literature doesn’t change anything anyway and is therefore harmless? On the contrary, the criticism voiced in books is seen as an example of the liberality of Western society, but what is often overlooked is the fact that criticism isn’t worth very much when it remains between the covers of a book.

At the same time, he takes a nuanced stance on the purpose and process of literature. He doesn’t endorse merely researching people’s problems to come up with books. He believes in authors writing about their own experiences.

It is not at all my opinion that writers should do market research before they start writing a book, that is, that they should find out what as many readers as possible want to hear. That happens often in the East and in the West, and usually, when it happens, trivial literature emerges in both places. It is also not my opinion that literature should be permitted to ignore the needs of readers or pretend that these needs exist on a lower level and are unworthy of its attention. And, if I might be permitted such a sweeping generalisation, this happens more often than not with Western literature. When I use the word literature here, I mean what is deemed ‘great literature’. I think this is an important reason why literature in the West is mainly a matter for intellectuals and not a matter for farmers and workers and other employees. These people often feel abandoned by books and that’s why they pick up things that might look like books but really aren’t.

I am convinced that good and important books don’t come into being when an author examines what problems people have and then thoroughly researches those problems and those people and then writes about it. That is how travel writing, which is really only writing about other people’s concerns, come into being but not important literature. I think good books only come into being when authors write about their own experiences, about their own misfortune or luck, their own doubts and discontents and hopes.

But he feels that writers in the west were divorced from the lives of the common people, preventing them from writing literature that makes an impact. He gives a telling statistic that portrays the nature of the society in East Germany, and adds that this gets completely reversed in the West.

“When I do ten readings in the GDR, the breakdown looks like this: I read three times at universities, once in a village in front of farmers, and six times in factories in front of workers and other employees.“

This is a striking feature that I found in the people featured in Svetlana Alexievich’s works too, centered around the erstwhile Soviet Union. Irrespective of their nature of jobs, almost everyone talks about literature, draws comparison with characters and situations from literary works from Pushkin to Solzhenitsyn.

Jurek Becker acknowledges the limitations of a writer. He feels that the writer has to revel in those limitations. For him, the writer is not the man who knows the way but one who seeks to find the way.

I do not want to claim that what makes a writer good is knowing exactly what is necessary and what isn’t and being able to push for that in one’s books. I do believe that a certain kind of ignorance, a ‘non-knowledge’ or ‘non-understanding’, just like a certain kind of ambition, motivates the creative human being to abolish it. It would make no sense at all to expect answers and answers only from books. In the East and in the West, what writers probably have in common is that they are seekers. Often, their literature is nothing but an attempt to find their way in the midst of the general sense of helplessness and to live in it.

He also has an interesting take on literary criticism:

You are all ornithologists and I am a bird. It is known that a constellation such as this can- and perhaps even must- present communication problems. It is also known that ornithologists try to understand the language of birds, but not vice versa. The birds indeed are normally a little bit better at chirping and a little better at flying- but that’s a different story. At any rate, I’ve never heard of a nightingale in a zoo being promoted to the director of an aviary. In a word – I absolutely don’t consider you incompetent to speak about the question which were under discussion- rather myself. You will hear my own views about my book- views that by no means have to be the established truth. They may be random or shallow or even both. And I even think it’s probably that after our discussion I will know more about a book of mine that I know now. But I do not think it is probable that the book would have been better if I had known all that beforehand. Such is my confused relationship to literary criticism.

Jurek Becker’s comes out as a voice that is unique and enlightening. I resolve to keep my ears open to hearing such voices that I haven’t heard before. And I am so glad that there are still public libraries where such wonderful voices are floating around, and we only need to poke our ears to pluck one at random.