Jammu and Kashmir has faced many wars, terrorism and people’s protests ever since India gained independence. Today, this land is encountering another major political challenge. A state, which was given special status, has lost its special status, and moreover, has lost the status of a state, being split into two Union Territories. The political leaders of Kashmir and a few thousand people have been imprisoned. More armed forces have been sent to Kashmir, which was already one of the most militarized zones in the world. Opposition leaders have been prevented from entering Kashmir. Most shops have been shut for almost two months. Mobile lines and internet have been largely cut-off. Access to the media has been restricted. An unproclaimed state of emergency is underway since the first week of August, 2019.

The accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India was done under special circumstances, unlike any other Indian state. The Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir, Hari Singh, belonged to the Hindu Dogra community. But the majority of people in his kingdom were Muslims. The valley of Kashmir had been sold by the British in 1846, under the Treaty of Amritsar, to his great-grandfather, Gulab Singh, then the ruler of Jammu, a feudatory of Punjab, for helping the British to defeat the Sikh army. Eventually the Dogras came to rule over Jammu, Kashmir, Ladakh, Baltistan, and Gilgit. Jammu and Kashmir was one of the largest Muslim majority regions in the Indian subcontinent. There was a festering resentment amongst the Muslims, since Rajputs from Jammu and other Hindus from outside the state were occupying positions of power. A ‘Kashmir for the Kashmiris’ movement was started, sponsored by the more educated Kashmiri Pandits. But when the Kashmiri Pandits also started improving their status in government service, ‘this aggravated the Muslims still further’. By the 1930s and 40s, Sheikh Abdullah had emerged as the most popular people’s leader in Kashmir. He had helped found All-Jammu Kashmir Muslim Conference in 1932 but later gave it a secular character, forming the National Conference, including the Sikhs and Hindus. He developed a close rapport with Jawaharlal Nehru and the Indian National Congress. Breaking with Abdullah, the Muslim Conference was revived by Ghulam Abbas, a Muslim from Jammu, but it could not match the popularity of the National Conference. Sheikh Abdullah developed a ‘New Kashmir’ manifesto, which was considered to be ‘one of the most advanced socialist programmes of its time’. The manifesto focussed on giving ‘land to the tiller’ and helped ‘the leadership to divert the minds of the majority of people from the communal issues to economic ones.’ Abdullah won the support of the Indian National Congress for the manifesto.

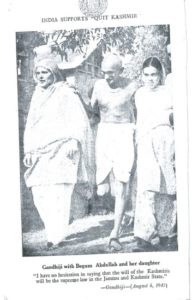

Later, National Conference launched a ‘Quit Kashmir’ agitation against the Maharaja in 1946. The Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Ram Chandra Kak, imposed martial law. Sheikh Abdullah was imprisoned when he attempted to go to Delhi to meet Nehru. Nehru went to Kashmir in June, 1946, to defend Abdullah; he was barred from entering the State, and when he persisted by standing at the border for five hours, he was let in but was arrested and detained in a dak-bungalow. However, Maulana Azad, the then President of the Congress, and Gandhi asked Nehru to come back to India on account of important discussions on the Cabinet Mission plan, telling him he was free to go at a later date. Nehru later went to Kashmir again, in July 1946, to attend part of Abdullah’s trial but could not meet the Maharaja. He had promised to come back but could not return. On the eve of partition, it was felt that his visit would be seen as a political move to sway Kashmir to India. Gandhi offered to go in his place. Mountbatten also visited Kashmir. After a number of vacillating exchanges between Mountbatten, Nehru, Patel and Gandhi, an exasperated Nehru wrote to Gandhi, “As between visiting Kashmir when my people need me there and being Prime Minister, I prefer the former.” [July 28, 1947]. Gandhi finally went to Kashmir on 1st August, 1947. He agreed not to give any political speeches but was allowed to conduct public prayer.

Two days before he started for Kashmir, he said at a prayer meeting in Delhi, “The people of Kashmir should be asked whether they want to join Pakistan or India. Let them do as they want. The ruler is nothing. The people are everything. The ruler will be dead one of these days but the people will remain.” [Jul 29, 1947]

On his first day at Srinagar, the city was illuminated to celebrate the restoration of Gilgit of Kashmir. Pyarelal writes, in The Last Phase, “‘What are these illuminations for?’ Gandhiji asked. On being told the reason, he remarked: ‘A great mistake. They should have taken this opportunity immediately to proclaim autonomy for Gilgit within Kashmir.’ Almost hundred per cent Muslim in its population, Gilgit had thoroughly been saturated with the separatist tradition sedulously fostered under the Political Department’s regime. In a flash Gandhiji saw the seeds of future trouble in an unqualified inclusion of Gilgit in Kashmir.” Gandhi met the Maharaja, the wife of Sheikh Abdullah and other functionaries of the National Conference. ‘A gathering of nearly 5,000 Kashmiri women had been waiting since 11 o’clock in the morning for Gandhiji. They insisted upon his darshan. This necessitated another difficult drive at 8 o’clock in the evening.’ The next day he was driven down to Jammu. “India will be free on the 15th of August, what of Kashmir?” a deputation of workers asked him at Jammu. “That will depend on the people of Kashmir,” Gandhiji replied. They all wanted to know whether Kashmir would join the Union or Pakistan. “That again,” answered Gandhiji, “should be decided by the will of the Kashmiris.”

Gandhi sent a note to Nehru and Patel, in which he said he had told the Prime Minister about his unpopularity among the people, and he had agreed to resign if the Maharaja wished him to. He added about his meeting with Maharaja and his heir:

“Both admitted that with the lapse of British Paramountcy the true Paramountcy of the people of Kashmir would commence. However much they might wish to join the Union, they would have to make the choice in accordance with the wishes of the people. How they could be determined was not discussed at that interview…

Bakshi (Ghulam Mohammad) was most sanguine that the result of the free vote of the people, whether on the adult franchise or on the existing register, would be in favour of Kashmir joining the Union provided of course that Sheikh Abdullah and his co-prisoners were released, all bans were removed and the present Prime Minister was not in power. Probably he echoed the general sentiment. I studied the Amritsar treaty properly called ‘sale deed’. I presume it lapses on the 15th instant. To whom does the State revert? Does it not go to the people ?” [Aug 6, 1947]

While speaking at a refugee camp in Wah on his way back, he said, “common sense dictated that the will of the Kashmiris should decide the fate of Kashmir and Jammu. The sooner it was done the better. How the will of the people would be determined was a fair question. He hoped that the question would be decided between the two Dominions, the Maharaja Saheb and the Kashmiris. If the four could come to a joint decision, much trouble would be avoided. After all Kashmir was a big State; it had the greatest strategic value, perhaps in all India.” [Aug 5, 1947]

Gandhi was consistent in his advocacy of listening to the people’s will, and at the same time, wished to avoid the balkanisation of India. Earlier, on June 24th, 1947, he had spoken at a prayer meeting about the attempts by C.P.Ramaswamy Iyer, the Diwan of Travoncore, to keep Travancore independent.

“Sir C. P. says that Gandhi and the Congress are all too willing to grant independence to N.W.F.P. but not to Travancore. How can a learned man like Sir. C. P. say such a silly thing? If Travancore becomes independent then Hyderabad, Kashmir, Indore and other States will also declare themselves independent and India will be Balkanized. […] In N. W. F. P. it is the voice of the people. But in Travancore it is a Maharaja and his Prime Minister speaking on behalf of the Hindus. Sir C. P. cannot throw dust into people’s eyes by advancing the example of N.W.F.P. I would suggest to Sir C. P. that Travancore should come into the Constituent Assembly.”

Earlier, in an interview with Sir M. Derling in April, 1947, he had said presciently,

“It hurts me to talk about the partition of the country. What will be the plight of a body if it is dismembered? Similarly, dismemberment of a prosperous country like India will utterly ruin the people. Today it is the country which is being divided, tomorrow it may be Kashmir and the day after it may be the State of Junagadh in the remote corner of Kathiawar. How is it all possible? Let the whole of India be handed over to the League. I would not mind it. That is why I believe that if, after the exit of the British power, the people of India are not awakened, India will become the battle-ground for the Princes to fight among themselves and the big ones among them will try to gain sovereignty by swallowing up the smaller ones.” [Apr 8, 1947]. Handing over the rule to Muslim League was not a mere rhetoric. He had already made a similar proposal to Lord Mountbatten and the Congress leaders.

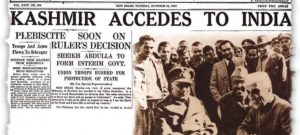

After the partition and independence of India, neither the Maharaja nor a majority of the Muslim population in Kashmir wanted to accede to Pakistan, and the Maharaja chose to be independent. But Pakistan considered this to be a serious loss. The Maharaja replaced Prime Minister, Kak, with M.C.Mahajan. Srinath Raghavan writes in his book, War and Peace in Modern India, “M.C. Mahajan, met Patel and Nehru, and informed them that the maharaja was willing to accede but wanted political reforms to be deferred. Nehru insisted that Sheikh Abdullah, who was incarcerated by the Kashmir authorities, should be released and that a popular government be immediately installed; only then should Kashmir declare accession to India. On 29 September Sheikh Abdullah was set free.”

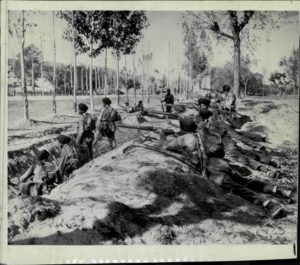

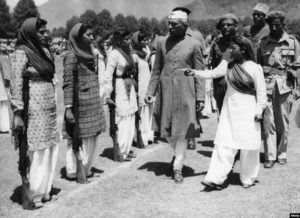

With indirect support from Pakistan, Afridi tribesmen from the North West Frontier Province, invaded Kashmir. ‘On 22 October 1947 nearly 5000 tribesmen seized Muzaffarabad, then Domel, Uri; and the raiders surged towards Srinagar. Two days later a beleaguered maharaja formally offered to accede to India and requested Delhi for military assistance.’ The Kashmiris, since they had largely been dependent on the British army, did not have adequate military expertise or weapons. Margaret Bourke-White, the American photo-journalist, who traveled through that region during that time, writes in her book, Halfway to Freedom, “With little but sticks and clubs and their bare hands, the volunteer People’s Army held their besieged capital…” The Maharaja of Kashmir signed the Instrument of Accession on 27th October, 1947. Special concessions were provided to Kashmir. These concessions were later incorporated into the Article 370 of the Indian Constitution. The Indian government was then inclined to accept the accession of Kashmir ‘subject to the proviso that the peoples’ wishes would be ascertained following the restoration of status quo ante.’ Sheikh Abdullah had also supported the accession and was shaping public opinion in favor of it. Indian forces were airlifted to Kashmir, and they arrived in time to defend Srinagar.

There were issues related to accession in Junagadh and Hyderabad too. These states were ruled by Muslim rulers, who did not want to accede to India, but the population was largely Hindu. When Mountbatten and Jinnah met at Lahore on 1 November, 1947, they spent over three hours discussing Junagadh, Hyderabad, and Kashmir. India wanted Pakistan to agree that ‘where the Ruler of a state does not belong to the community to which the majority of his subjects belong, and where the state has not acceded to that Dominion whose majority community is the same as the state’s, the question whether the state should finally accede to one or the other of the Dominions should in all cases be decided by an impartial reference to the will of the people.’ Nehru was willing to conduct a UN-supervised plebiscite ‘after complete law and order have been restored’. But Jinnah declined. Srinath Raghavan writes on the possible reasons for Jinnah’s stand, ‘First, Jinnah believed that despite India’s intervention the invasion might yet succeed; this explains his desire to send more tribesmen to Kashmir. […] Second, Jinnah was not oblivious of the possibility that, owing to the havoc wrought by the tribesmen, Pakistan might lose a plebiscite.’

Outside Kashmir too, all along the border areas of India, there was enormous chaos, and large scale massacres were rampant. Muslims from India and Hindus and Sikhs from Pakistan were forced to migrate on a scale unprecedented in history. Many thousands of Hindu, Sikh and Muslim refugees, having lost their houses, wealth and relatives, were gathered in New Delhi.

In this complex political chaos, Gandhi moved to New Delhi after helping to bring a relative peace in Calcutta. He kept meeting the people, and, everyday, addressed large gatherings during his prayer meetings. He also spoke about Kashmir.

Gandhi felt a great darkness had enveloped him during his final years. He saw his ahimsa being put to its most stringent test. He also realized that while he considered ahimsa to be a creed, a way of life and the ultimate truth, his longtime associates had only used it only as a strategy and a tool to secure independence. Having won the freedom without swords and blood, the people were bathing their land in blood. The country was partitioned against his wishes. He did not hesitate to concede that the Indian Independence movement was not truly non-violent. Yet, amidst all this darkness, Gandhi did not lose hope in non-violence. Some of the most remarkable achievements were made through non-violence in Noakhali and Calcutta, when the region was being swept by a murderous rage and bigotry. Enormous losses, on the scale of the Western India, were averted to an extent.

But Gandhi did not protest when the Indian military forces were sent to protect Kashmir. Gandhi, who had once considered that independent India did not need an armed military, did not oppose vehemently when armed forces were sent to Kashmir. He sometimes expressed his helplessness. It needs to be explored if Gandhi, who had made some compromises to his creed of non-violence when he was involved in the South African wars and the First World War, again made compromises in his stance on Kashmir. We have to concede that Gandhi, who had prepared the Indians to non-violently oppose even Hitler and the Japanese forces during the second World War, slackened his strict insistence on non-violence, when Kashmir was under siege. Gandhi always held it was better to fight a powerful opponent with arms than to die like cowards without resisting. He emphasized that view again, now. He said, “Supposing an army of a lakh of armed Afridis invaded the place and a handful of people offered armed resistance in order to protect the innocent children and women and died fighting, then they could be called non-violent in spite of their using arms.” While he was extremely averse to clandestine attacks on individuals to assassinate them, he did praise the valor of people like Subhas Chandra Bose who had waged an armed war against mighty opponents. And he claimed non-violence was far greater than armed resistance. But to see him terming this also ‘non-violent in spite of their using arms’ is surprising. He had written once, ‘It is not possible for a modern State based on force, non- violently to resist forces of disorder, whether external or internal. […] It is claimed that a State can be based on non- violence, i. e., it can offer non-violent resistance against a world combination based on armed force.’ [May 2: 1946, Harijan]. He was also aware there was no one to listen to his call for pure non-violence when the country and the people were in such turmoil. We can see this as an instance when, instead of letting thousands of people die to uphold his creed, he decided to not place his creed as an impediment in the way of saving Kashmir.

The question was asked of Gandhi also if it was right for him, who had explored great heights of ahimsa, to support war? In an interview to Kingsley Martin, he quipped, he was not in charge of the Government and therefore could not guide their policies; nor did he think that the members of the present Government believed in non-violence. He added, “the truly non-violent man could never hold power himself. He derived power from the people whom he served. For such a man or such a government, a non-violent army would be a perfect possibility. The voters then would themselves say, ‘We do not want any military for our defense.’ A non-violent army would fight against all injustice or attack but with clean weapons. Non-violence did not signify that man must not fight against the enemy and by enemy was meant the evil which men did, not human beings themselves.” He went on to say that if he were the leader of Kashmir, like Sheikh Abdullah, he would have such an army but Sheikh Abdullah quite honestly and humbly thought otherwise.

If he had the opportunity to go to Kashmir again, which was not possible due to the prevailing conditions in Delhi, he might have taken a different approach. Pyarelal mentions, “Even in the matter of Kashmir, though he had expressed his admiration for the courage of the fighters and the unity of purpose and cohesion shown by all sections of the population to stem the tide of invasion, he felt that a golden opportunity had been let slip. The Indian Government had a perfect right, as the world understands right, to send and it did what was just the right thing for it to do in the circumstances in sending troops to the defense of Kashmir at the request of the Maharaja backed by that of the National Conference. But that again was not his way. He would have liked to see the whole of India rally to the side of the defenders in non-violent defense of their soil against aggression. The aggression was so unprovoked, he felt, and the case of the defenders so manifestly just that if the people of Kashmir had resisted the invasion non-violently to the last, it would have won the admiration and sympathy of the whole world. ‘I would like to go to Kashmir myself,’ he once remarked to me while going to meet Lord Mountbatten towards the close of December. ‘I am sure if the people followed my way, victory would be theirs.’ With a sigh he added: ‘If only the situation in Delhi would let me.’” Gandhi had told Pyarelal again [after the fast in January 1948], ‘something about his going to Kashmir, if he was successful in Delhi, to see what non-violence of his conception could do there.’

Gandhi also sent his Parsi friends, Jehangir Patel and Dr.Dinshaw Mehta, as his personal emissaries to Pakistan to hold talks with Jinnah, Liaquat Ali Khan and others. They made considerable progress there. A tribunal consisting of the Prime Ministers of India and Pakistan to resolve all outstanding issues, including Kashmir, was mooted. If the formula was accepted, the United Nations Organization could be asked to suspend the discussions on Kashmir. A visit by Gandhi to Pakistan was planned. “Tentative dates for Gandhi’s arrival were fixed – February 8th or 9th. In Delhi, Gandhi was visited by a Pakistani Muslim who painted an enthusiastic word-picture of ‘a fifty-mile procession of Hindus returning to Pakistan with Gandhi himself at the head’. The idea delighted Gandhi. Better days, it seemed, were about to dawn,” wrote Jehangir Patel and Marjorie Sykes. Gandhi also referred to this visit, in a letter, “I have sent Jehangir Patel and Dinshaw Mehta to have talks with Jinnah, Liaquat Ali and others. I am hoping that I shall get considerable help from Suhrawardy in my projected visit to Pakistan. But all this is day- dreaming.” [January 24, 1948]. This ambitious plan, which rested on the moral influence of the Mahatma, was snuffed by three bullets of an assassin.

Gandhi’s speeches and interviews during this period show how while a war was raging outside, another war was raging inside him too, between his pragmatism and idealism. He told Vincent Sheen, two days before his assassination, “See what India is doing. See what is happening in Kashmir. I cannot deny that it is with my tacit consent. They would not lend ear to my counsel. Yet, if they were sick of it, I could today point them a way.”

Many of his speeches during this period were delivered in explosive circumstances, in front of people who were feeling forlorn and enraged. Gandhi spoke to give them solace and encouragement and hope, and to avoid violence and to share news. They were mostly delivered in colloquial Hindi and later translated into English. Hence they may lack the meticulousness and precision of his other writings. Yet, we can see his unique perspectives, sharp words, irrefutable logic and love for people gleaming at many places.

We can also observe some common threads emerging from these speeches.

Firstly, he emphasized that people’s opinion was paramount, be it in Kashmir or other territories, and neither India nor Pakistan should force them to accede. Gandhi supported the accession of the Muslim majority State of Kashmir to India, more because of Sheikh Abdullah than the Maharaja. He believed Sheikh Abdullah had the backing of all Kashmiris. “If it had been only the Maharaja who had wanted to accede to the Indian Union, I could never support such an act. The Union Government agreed to the accession for the time being because both the Maharaja and Sheikh Abdullah, who is the representative of the people of Jammu and Kashmir, wanted it. Sheikh Abdullah came forward because he claims to represent not only the Muslims but the entire masses in Kashmir.” [Nov 11, 1947]

When it came to listening to the will of the people, he thought it was essential and did not base his principle on time, place and gains.

“It makes no difference to me whether it is the question of Kashmir or Hyderabad or Junagadh. Let no one be forced into anything. Let there be no coercion. But I must respectfully submit that today Kashmir is not ruled by its Maharaja. In other States too there are no Princes as we used to know them. They were the creation of the British. Now the British have gone. They had installed them as rulers because they could rule through them and exercise power. Kashmir has still to establish popular rule in the State. The same is the case with other States like Hyderabad and Junagadh. In my view there is no difference between them. Real rulers of the States are its people. If the people of Kashmir are in favor of opting for Pakistan, no power on earth can stop them from doing so. But they should be left free to decide for themselves. The people cannot be attacked and forced by burning their villages. If the people of Kashmir, in spite of its Muslim majority, wish to accede to India no one can stop them.

The Pakistan Government should stop its people if they are going there to force the people of Kashmir. If it fails to do that, it will have to shoulder the entire blame. If the people of the Indian Union are going there to force the Kashmiris, they should be stopped, too, and they should stop by themselves. About this I have no doubt at all.” [Oct 26, 1947]

“…only the people of a particular State have a legal right to accede to one of the Unions. If the Provisional Government does not represent the people of Junagadh at any stage, it is merely a group of people who are unjustly occupying seats of power in the State and it should be driven out by both the Dominions. If any ruler joins any of the Unions in his personal capacity, the Dominion cannot stand before the world to justify his action. From this point of view, I think that the Nawab’s accession has been baseless from the very beginning till it is proved that the people of the State have given their consent to the accession by the Nawab. The dispute as to which Union Junagadh would finally accede to can be resolved only by taking public opinion, that is, by referendum. This task should be properly carried out and should not involve violence or show of violence. The stand taken by the Government of Pakistan and now also by the Prime Minister of Junagadh, has created a strange situation. Who was to decide whether Pakistan was in the right or the Union Government? One cannot even think that it can be decided by an appeal to the sword. The only honourable way is to decide the matter through arbitration. We can find many impartial individuals in the country itself but, if the parties concerned cannot agree to arbitration by Indians, I for one will have no objection to any impartial person from any part of the world.

Whatever I have said about Junagadh equally applies to Kashmir and Hyderabad. Neither the Maharaja of Kashmir nor the Nizam of Hyderabad has any authority to accede to either Union without the consent of his people.” [Nov 11, 1947]

Secondly, Gandhi was greatly impressed by the unity displayed by the Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims in Kashmir. About an earlier Sultan of Kashmir, he had said, “In days gone by when, accompanied by Hindus, Jainuluddin set out on a pilgrimage to Kashi, he got repaired all derelict temples he passed on the way” [June 12, 1947]. He saw Kashmir as the place where the idea of partition will be proven wrong. He could have thought of the accession of Kashmir to India as a victory for secular thinking. “The poison which has spread amongst us should never have spread. Through Kashmir that poison might be removed from us. If they make such a sacrifice in Kashmir to remove that poison, then our eyes also would be opened,” he said. “It is my prayer that in the present darkness in the country Kashmir may become the star that provides light,” he hoped and prayed [Dec 29, 1947]. He was greatly distressed when the Hindu and Sikhs attacked Muslims in Jammu.

Thirdly, it is for this same reason, his admiration for its secularist nature, that he opposed any suggestion to partition Jammu and Kashmir. It is evident that he thought partitioning Jammu and Kashmir along religious lines tantamounts to India accepting the principle of partition. “…Jammu and Kashmir is one State. It cannot be partitioned. If we start the process of partitioning where is it going to end? It is enough and more than enough that India has been partitioned into two. If we partition Kashmir, why not other States?“ he asked [Dec 25, 1947]. This was his strong position.

Fourthly, we can also observe the faith and admiration he had for one person, Sheikh Abdulla, influencing his position on Kashmir. Many Kashmiris were inspired by Abdulla to fight and die bravely. History has forgotten the martyrdom of people like Mir Maqbool Sherwani. Gandhi records that history in his speeches. Margaret Bourke-White gives in her book, a more detailed narration of the fight of Maqbool and his crucification-like death. (Mulk Raj Anand’s novel ‘Death Of A Hero’ was also based on Shewani’s life.) Margaret was the last journalist to have interviewed Gandhi. She too had seen Sheikh Abdullah in action and written highly of him. She felt that the People’s government of Sheikh Abdullah of that time was more progressive and secular than the Indian government and acted with speed on issues like land reforms. Therefore, it should not surprise us that Gandhi was attracted by Abdullah. But, in his last letter on Kashmir [Jan 28, 1948, addressee not given in CWMG], he hinted at the danger lurking in taking a position that banked too much on one person. “Sheikh Abdullah is a brave man. But one wonders whether he may not betray in the end. I hold that no man can betray another, for ultimately one is betrayed by oneself. Therefore on this account I have no worry.”

Fifthly, Gandhi initially advocated using an impartial arbitrator from within India (or Pakistan) to resolve the disputes over states like Kashmir, and if no trusted person is found here, an impartial person from any part of the world could be brought in. But later, he was more strongly opposed to the idea of seeking the intervention of outsiders. He did not condemn the act of India taking the Kashmir issue to the United Nations. He accepted that India was running out of options. But he found it difficult to endorse it. “ Will not the Governments of Pakistan and the Union come together and decide the issue with the help of impartial Indians? Is there no one in India who is impartial? I am sure we have not become bankrupt to that extent,” he lamented. “About Kashmir I feel that there is no need for us to go to Lake Success [UNO]. Still we shall see what comes about,” he wrote in a letter [Jan 27, 1948]. Pyarelal also observed, referring to an incident on the same day [Jan 27], “Gandhi was very disappointed with the way in which the Security Council of UNO was dealing with the Kashmir question. Instead of considering India’s complaint and getting the aggression vacated, the stage was being set to ask India to withdraw her troops from Kashmir as preliminary to the holding of a plebiscite which would decide the future of Kashmir. It seemed to have become a packed body, where falsehood and prevarication enjoyed a high premium. ‘Today they are preparing to put Pandit Nehru’s Government in the dock,’ he remarked during his journey back from dargah. ‘Unless we are extremely wary, we shall come out with our name tarnished.’

I hope this selection of the thoughts of Gandhi will help us in getting a deeper understanding of Gandhi and the tumultuous period when Kashmir acceded to India.

Ramachandra Guha, wrote in the Telegraph [Aug 17,2019], “Had Gandhi been alive, he would perhaps have been most appalled by three events in the modern history of Kashmir: the arrest of Sheikh Abdullah by the Nehru government in 1953, the ethnic cleansing of the Pandits by Islamic jihadists in 1989-90, and the unilateral abrogation of Article 370 and the savage crackdown by the Narendra Modi government on Kashmiris in 2019.”

We can make some more inferences from the views of Gandhi, not limited to what he could articulate during this period, and speculate on how Gandhi would have viewed some of the developments in Kashmir, since August 2019.

- Gandhi would have held Pakistan responsible for cross-border terrorism but never make that an excuse for India to subjugate its own people. He would have revolted against the arrest of the entire political leadership in Kashmir.

- Gandhi could never have been able to approve the unilateral abrogation of Article 370. He could never have deemed the governor appointed by the Central Government as a substitute for a State Government elected by the people or the Constituent Assembly. Even if passes legal muster, he would have considered it morally reprehensible.

- The idealist Gandhi would have been extremely uncomfortable with the partition of Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir. “I have heard people talking in whispers that Kashmir could be divided. Jammu would come to the Hindus and the Muslims would have Kashmir. I cannot even think of such divided loyalty and division of the Indian States into several parts,” Gandhi had said [Nov 11, 1947]. But if he was convinced that it was the dominant will of the people of Ladakh, the pragmatic Gandhi may have come to terms with it.

- Gandhi would have been repulsed by the conversion of a state into two Union Territories. If anything, he would have argued for more decentralization and more powers to a region beset with internal problems.

- He would have been extremely pained by the heavy militarization of both sides of Kashmir. He would have been appalled by the denial of civil rights to a whole people for such a long period. He summarized his idea on a martial law, when he said, “It has been suggested that Punjab should be placed under martial law. I have seen Punjab once placed under martial law. I know what martial law means. It cannot change men’s hearts. I shall still say that if Muslims want to save Islam, Hindus Hinduism and the Sikhs their Gurudwaras, they must together resolve that they will not fight…” [June 24, 1947]

- Gandhi would have felt most let down by the forced exodus of Kashmiri Pandits from Kashmir. This was a big blow to his vision of an ideal secular society in Kashmir, which ‘may become the star that provides light.’ He would urge the civil society in Kashmir to welcome the Kashmiri Pandits back, reinstate them in their own localities and protect them against any insurgent attacks. At the same time, he would not allow what happened to Kashmiri Pandits thirty years ago to become a justification for what is unleashed on Kashmir now.

- A plebiscite in the whole of Jammu and Kashmir, after withdrawal of the Pakistani forces, as proposed in 1947-48 has become increasingly infeasible. Over the next few years, Nehru considered various ways in which a plebiscite could be held but none of them materialized, due to disagreements with Pakistan. Gandhi might have still advocated means to listen to the will of the people in the Indian Administered Kashmir, irrespective of the stance of Pakistan, and do everything possible to convince the people that it was best to remain with India.

Gandhi’s ideas on Kashmir, though far removed in time, still have the power to lead us towards light, not only on Kashmir but on various other issues as well. His emphasis on truth, non-violence and compassion are timeless and universal.

References:

- The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi

- Margaret Bourke-White, Halfway to Freedom, New York: Simon And Schuster, 1949.

- Srinath Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2010.

- Pyarelal, The Last Phase, Volume 2, Ahmedabad:Navajivan Publishing House, 1958.

- Jehangir P. Patel and Marjorie Sykes, Gandhi – His Gift of the Fight, Rasulia: Friends Rural Centre, 1987

- Victoria Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War, Diane Publishing Company, 2003.

- Nyla Ali Khan, The Parchment of Kashmir, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2012.

Note:

(This essay appears as the Introduction to the book, ‘War and Ahimsa: Gandhi on Kashmir’, which is yet to be published in English. It has been published in Tamil by Yaavarum Publication as ‘போரும் அகிம்சையும்: காஷ்மீர் குறித்து காந்தி’.)