To Read:

First Part : https://tamizhini.in/2018/11/14/the-ba-in-the-bapu-kannan-t/

Second Part : https://tamizhini.in/2019/01/13/the-ba-in-the-bapu-part-2-kannan-t/

(9)

After a long period of personal and political transformation, the Gandhi family left South Africa in July, 1914. While the rest of the party went to India directly, Gandhi and Kasturba first went to England, along with Kallenbach, to meet Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who was recuperating there.

The uncertain young lawyer, who had come to South Africa had turned into an important political leader, not just in South Africa, but one who was expected to make an impact in India, and whose political weapons were seen to be of relevance for the whole world. The typical Gujarati housewife had turned into a selfless mother who had seen three of her sons go to jail, an efficient administrator of multi-racial, multi-caste communities in her ashrams, and a courageous leader in her own right, having led a group of women to court arrest.

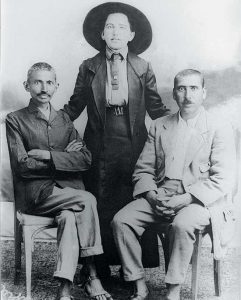

Gandhi and Kallenbach

When their boat was in the English Channel, World War I was declared. Gandhi, again, offered to setup an ambulance corps to help the British Empire. However, he fell ill with pleurisy and a damaged leg. Kasturba had to tend to him in a cold and foggy country, completely alien for her. Finally, they set out to India in December, 1914, leaving behind Kallenbach, who was barred from travelling to India due to his German roots. It wasn’t surprising that Gandhi and Kallenbach, who had setup the Tolstoy Farm together, and become intimate friends, felt pangs of separation. But Gandhi soon wrote to Kallenbach from India, “You will be surprised that Mrs. Gandhi has developed a passion for you. She thinks of you at every turn. She thinks that our life is incomplete without you. This is not my favorable construction method but this is how it is happening with her just now.”

Kasturba had started accepting Gandhi’s friends as her own. She, occasionally, even partook in his food fads. ‘It surprises me with what tenacity she holds on to a purely fruitarian diet and mostly uncooked,’ wrote Gandhi. She was probably baffled by the continuous evolution of her husband’s dress, as much as his views. The man who had insisted on making his family wear modern clothes when they had left India for South Africa, was now wearing the dress of indentured Indians, while on the ship to India. ‘Today I have worn somewhat to Mrs. Gandhi’s disgust, the Indian dress I used to in South Africa. The passengers looked surprised as I appeared on the deck but I think the surprise has passed away.’ Off the ship, Gandhi started wearing the plain clothes of Kathiawar middle class men. This was to undergo further change, till Gandhi reduced it to only the loin cloth and shawl.

During the journey to India, Kasturba had the rare opportunity to be alone with her husband for a long stretch of time, probably for the first and the last time. Her husband was learning Bengali, in anticipation of joining his extended family who were then at Tagore’s Shantiniketan. In India, there were many meetings held to honor the Gandhis, at Bombay, Ahmedabad, Madras and Calcutta. Eminent leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, and Sir Pherozeshah Mehta presided over these meetings. Bombay Chronicle reported Gandhi’s speech at one such meeting at Mt.Petit, Bombay: ‘They had also honored Mrs. Gandhi as the wife of the great Gandhi. He had no knowledge of the great Gandhi, but he could say that she could tell them more about the sufferings of women who rushed with babies to jail and who had now joined the majority than he could.’

On the advice of Gokhale, Gandhi embarked on a long tour of the country, and Kasturba accompanied him to many places. Though his mentor passed away, he continued to follow his advice. Gandhi took to travelling by third class compartments on trains. He notes in his autobiography, how he made the rare exception of allowing a friend to help him take Kasturba to the second class bath room.

I hesitated to accept the courteous offer. I knew that my wife had no right to avail herself of the second class bathroom, But I ultimately connived at the impropriety. This, I know, does not become a votary of truth. Not that my wife was eager to use the bath room, but a husband’s partiality for his wife got the better of his partiality for Truth.

Gandhi made complaints about the condition of the third class compartment facilities to the railway authorities. He traveled with Kasturba as deck passengers on a ship to Burma. In his complaint to the Secretary, Passenger’s Grievance Committee at Rangoon, he mentioned, ‘Closets are filthy beyond description; closets allotted for females are often used by men; Mrs. Gandhi had to be specially accompanied each time she wanted to use the closets. There are, as a rule, no locks to the doors.’

Kasturba was learning it the hard way to be the Mahatma’s wife.

In May, 1915, Gandhi established the Satyagraha Ashram at Kochrab on the outskirts of Ahmedabad, in a bungalow rented out to him by a barrister, Jivanlal Desai. The Gandhi family and the other returnees from South Africa moved there. Gandhi introduced eleven vows to be taken by the inmates of the ashram: nonviolence, truth, non-stealing, chastity, non-possession, bread labour, control of the palate, fearlessness, respect for all religions, swadeshi and abolition of untouchability.

Kochrab Ashram, Ahmedabad

The last vow posed the severest test soon, in September 1915. Thakkarbapa, then a member of Gokhale’s Servants of India Society, had visited Kochrab Ashram. Soon he sent a letter stating that an untouchable family was desirous of joining the ashram, and whether they would accept them. Gandhi showed the letter to the ashramites. Though some of them welcomed the move, many objected. While caste barriers were set aside in South Africa far more easily, the resistance was stiffer in the ashram located amidst the conservative Gujarati Hindu society. Despite objections, he invited the family to stay with them. Dudhabhai and his wife Daniben took the ashram vows, and moved in, along with their infant daughter Lakshmi. A social boycott of the ashram and ashramites was in the offing. The businessmen of Ahmedabad stopped their monetary support to the ashram. There were twenty-five members at the ashram to be fed and supported. A major financial crisis was averted when a prominent businessman, Ambalal Sarabhai, made a covert donation of Rs.13000. However, the emotional turmoil inside the ashram continued. Maganlal Gandhi, unable to persuade his wife, Santokben, to accept Dudhabhai family, had to leave the ashram. It was decided that they spend six months in Madras, learn weaving there, and then return to the ashram, if they wished to. This was a huge blow to Gandhi. The industrious Maganlal was the man who bore the maximum responsibility in the running of the ashram. They returned, having, ‘washed their hearts clean of untouchability’.

But it was resistance from Kasturba herself that shook Gandhi. Gandhi stood his ground. Their tussle got captured in the various letters that Gandhi wrote to his friends. He wrote to Srinivasa Sastri that he told Kasturba they should part as good friends:

“When I took in Naiker, Mrs. Gandhi did not ‘kick’. Now I had to decide whether I was to take in a grown-up Gujarati Dhed with his wife. I decided to take him and she rebelled against it and so did another lady at the Ashram. There was quite a flutter in the Ashram. There is a flutter even in Ahmedabad. I have told Mrs. Gandhi she could leave me and we should part good friends. The step is momentous because it so links me with the suppressed classes mission that I might have at no distant time to carry out the idea of shifting to some Dhed quarters and sharing their life with the Dheds. It would mean much even for my staunchest co-workers. I have now given you the outline of the story. There is nothing grand about it. It is of importance to me because it enables me to demonstrate the efficacy of passive resistance in social questions and when I take the final step, it will embrace swaraj, etc.”

It was also evident that there was no line separating the private and public for Gandhi. He added in the same letter, ‘Please share this with Dr. Deva and any other member you please.’

Writing to Kallenbach, he elaborated on the earlier instance involving Naiker, contrasting the response with the current situation:

“You know what a Pariah is. He is what is called an untouchable. The widow’s son whom I have taken is a Pariah but that did not shock Mrs. Gandhi so much. Now I have taken one from our own parts and Mrs.Gandhi as also Maganlal’s wife were up in arms against me. They made my life miserable so far as they could. I told them they were not bound to stay with me. This irritated them the more. The storm has not yet subsided. I am however unmoved and comparatively calm. The step I have taken means a great deal. It may alter my life a bit, i.e., I may have to completely take up Pariah work, i.e., I might have to become a Pariah myself. We shall see. Anyway let my troubles brace you up if they can.”

In a letter to Narandas Gandhi, he wrote about when a person has to show firmness to deal with the objections of a spouse. He takes the position that the right to overrule invalid objections rests both with the husband and the wife.

“Worries from the side of one’s wife may be overcome only with gentle firmness. A husband or a wife has no right to obstruct the other in pursuit of a worthy aim. In the situation which has arisen, I indeed suffer outwardly but experience boundless inward happiness. I feel that it is only now that my life in India has started.”

Gandhi prevailed. As before, when they had a similar argument in a similar situation in South Africa, Kasturba yielded and stayed. To her credit, she overcame her inhibitions, and came to love the Dudhabhai family. Gandhi and Kasturba went on to adopt Lakshmi as their daughter. Lakshmi, later, in an interview, said that Kasturba and her mother got along well and did most of the kitchen work together. Lakshmi was left entirely in the charge of Gandhis after she turned five. She reports how well Ramdas and Devdas took care of her. She also says that Kasturba asked her to eat properly every day, ignoring Gandhi’s advice on diets. As with all his sons, Gandhi had displayed his demanding parenting style to her too, urging her to crop her hair in repentance for a minor transgression. She too went to jail in 1932. In 1933, she was married off to Marutayya, aka Maruti, a Brahmin from Madras. Both Gandhi and Kasturba were in prison at that time. Gandhi had once asked Kasturba to give all her gold to Lakshmi at the time of her marriage, but by the time she got married, Kasturba had no gold left with her. When Lakshmi’s husband died, leaving behind two children, she wanted to come back to live permanently at the ashram. But, since she refused to comply with the ashram rules that all her jewels and money be handed over to the ashram, she was denied permission to shift there. When, later, she made up her mind to move to Sevagram, Kasturba was no more, and Gandhi too never returned.

Lakshmi with Gandhi. Source: National Gandhi Museum, New Delhi.

(10)

Due to the persistent pursuance of Rajkumar Shukla, a farmer from Bihar, Gandhi visited Champaran to gather firsthand knowledge about the plight of peasants there, forced to cultivate the unprofitable indigo. Gandhi decided to camp in Champaran, and record the statements of all the peasants. He also saw the need for engaging in various other constructive activities in that area. He invited Kasturba and other associates from the ashram to Champaran. They started schools and taught sanitation to Champaran’s villagers.

‘Attacking Gandhi’s mission in a letter in The Statesman of Calcutta, a prominent white planter called Irwin objected to Kasturba’s presence in Champaran. Said Irwin: ‘During the absences of her lord and master at Home Rule and such-like functions, Mrs.Gandhi following in the footsteps of Mrs. Annie Besant, scatters similar advice broadcast, and has recently, under the shallow pretence of opening a school, started a bazaar in [a] dehat’. In his reply Gandhi said that Irwin had unchivalrously attacked one of the most innocent women walking on the face of the earth (and this I say although she happens to be my wife)’. ‘ [Mohandas, Rajmohan Gandhi]

In the same reply to The Statesman, Gandhi wrote more in defence of Kasturba, giving an insight into the nature of her initial work in Champaran:

A word only for my innocent wife who will never even know the wrong your correspondent has done her. If Mr. Irwin would enjoy the honour of being introduced to her he will soon find out that Mrs. Gandhi is a simple woman, almost unlettered, who knows nothing of the two bazaars mentioned by him, even as I knew nothing of them until very recently and some time after the establishment of the rival bazaar referred to by Mr. Irwin. He will then further assure himself that Mrs. Gandhi has had no hand in its establishment and is totally incapable of managing such a bazaar. Lastly, he will at once learn that Mrs. Gandhi’s time is occupied in cooking for and serving the teachers conducting the school established in the dehat (interior) in question, in distributing medical relief and in moving amongst the women of the dehat with a view to giving them an idea of simple hygiene. Mrs. Gandhi, I may add, has not learnt the art of making speeches or addressing letters to the Press.

Writing to other friends, he throws more light on her work. To Mille Polak, he wrote, “Mrs. Gandhi is in her element. She is going to assist at another school. This means life in the jungle. She does not mind it.”

To A.H.West, he wrote:

“In Bihar, besides watching the legislative activity, I am opening and managing schools. The teachers are as a rule married people. And both husband and wife work. We teach the village children, give the men lessons in hygiene and sanitation and see the village women, persuade them to break through the purdah and send their girls to our schools. And we give medical relief free of charge. Diseases are known and so are remedies. We, therefore, do not hesitate to entrust the work to untrained men and women provided they are reliable. For instance, Mrs. Gandhi is working at one such school and she freely distributes medicine. We have, perhaps, by this time relieved 3,000 malaria patients. We clean village wells and village roads and thus enlist villagers’ active co- operation. Three such schools have been opened and they train over 250 boys and girls under 12 years. The teachers are volunteers.”

Champaran saw the emergence of Gandhi on the active political stage of India. Champaran also was the place where many of his closest followers like Kripalani, Rajendra Prasad and Brajkishore Prasad emerged and took their first lessons in Satyagraha. And it was in Champaran that Kasturba further broadened the scope of her work, stepping outside the ashram activities.

“Mrs. Gandhi has developed remarkably. She has beautifully resigned herself to things she used to fight. But I must [not] describe things. You must see them for yourself,” Gandhi acknowledged her development, in a letter to his old secretary, Sonja Schlesin.

(11)

The Satyagraha Ashram was shifted to a vacant space on 55 bighas of land, along the Sabarmati river, close to the prison. More and more people were joining the ashram. ‘We decided to start by living under canvas, and having a tin shed for a kitchen, till permanent houses were built. There were now over forty souls, men, women and children, having our meals at a common kitchen. The whole conception about the removal was mine, the execution was as usual left to Maganlal.’ In addition to Maganlal, other key associates had started gathering around Gandhi in the ashram – Vinoba Bhave and Mahadev Desai, being the foremost. Other visitors from India and abroad started visiting the ashram. For instance, Esther Faering and Anne Marie Peterson, members of the staff of the Danish Missionary Society in South India, had visited Kochram Ashram as a preparation for their educational work. Esther later visited Sabarmati Ashram too, and grew to be like another daughter to Gandhi, and exchanged numerous letters. In later letters, Gandhi referred to her always as ‘My dear child’.

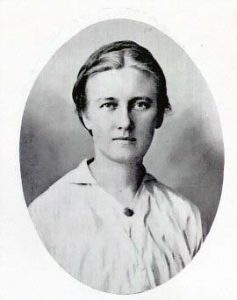

Esther Faering

Kasturba’s personal reputation was also growing. Mahadev Desai records the following exchange in his Diary:

Mrs. Jinrajdas (of the Theosophical Society of India) made Ba (Mrs.Kasturba Gandhi) a member of the All India Women’s Conference and sent a card intimating the fact. Gandhiji wrote to her:

“Mrs.Gandhi is an almost illiterate woman. She cannot even sign her name in English. Do you want mere names to adorn your register?”

Mrs. Jinrajdas wrote back in a loving and gentle retort.

To her Gandhiji replied:

“The sentence about Mrs.Gandhi’s signature in English was unhappily worded. The complete thought has not been given to it. Mrs.Gandhi is educated in any sense of the term. She can hardly read and write Gujarati. That she cannot even sign her name in English, was intended to convey to those who prize English education, the full measure of Mrs. Gandhi’s unfitness to become a member of an association who members are scholars, either in their own language or in English.”

In another letter to Rasikmani, Secretary, Hindu Stri Mandal, who had invited Kasturba to preside over their annual function, he again declined the invitation on her behalf.

I could read your letter to my wife only yesterday and hence the delay in replying. Kindly forgive me. Though we two are independent and have equal rights, we have decided our spheres of work for the sake of convenience. Moreover, at the time of our marriage, my wife was altogether illiterate. I gave her some education with great effort, but, for several reasons, I have not been able to do so to my satisfaction. It is not possible, therefore, for her to accept your proposal. I don’t think my wife can read out her speech from the chair. She will certainly not be able to prepare her own speech. She is not at all conversant with your activities and hence cannot say anything extempore either. Very regretfully, therefore, we have both to request you all to excuse us.

Gandhi here can be seen as an authoritative husband choosing which activities his wife must get engaged in. Or, one can see a protective husband trying to shield his wife from being drawn into activities, where she may be out of her depth.

Gandhi’s political work was increasingly keeping him away from the ashram from 1918 onwards. Her sons were also away from her. He wrote loving letters to her. He urged her to ‘look upon all the children as her own’. He told her ‘to give mother’s love and solace to Maganlal, who had left his home and parents to make my work his own.’

He tried to console her for the remonstrations she must have made for being left behind in the ashram.

[Nadiad]

July 31, 1918

BELOVED KASTUR,

Your being unhappy makes me unhappy. If it had been possible to bring ladies, I would have brought you. Why should you lose your head because I may have to go out? We have learnt to find our happiness in separation. If God has so willed, we shall meet again and live together. There are many useful things one can do in the Ashram and you are bound to keep happy if you occupy yourself with them.

A month later Gandhi fell seriously ill, and Kasturba convinced him to take goat’s milk. During the next year or two, their relationship seem to have also been very strained at times. Gandhi complains about her actions and attitude to a few close associates. Having convinced him on goat’s milk, she had also poked him on that. He writes to Maganlal,

Bombay

January 10, 1919

These days, I have been thinking so much about all sorts of things that I often feel a strong urge to share some of my thoughts with you all. But, thanks to physical weakness and mental torpor, I can neither write nor dictate. Today I cannot help dictating. In the changes I am making at present, my atma bears witness that I am showing no weakness. I am making them with a detached mind and out of my strength, the main purpose being to satisfy all of you and the other friends. I simply cannot bear to look at Ba’s face. The expression is often like that on the face of a meek cow and gives one the feeling, as a cow occasionally does, that in her own dumb manner she was saying something. I see, too, that there is selfishness in this suffering of hers; even so, her gentleness overpowers me and I feel inclined to relax in all matters in which I possibly may. Only four days ago, she was making herself miserable about milk, and, on the – impulse of the moment, asked me why, if I might not take cow’s milk, I would not take goat’s milk. This went home.

To Esther Faering, who had visited the ashram in January 1920, and he had to leave immediately, he wrote,

I would like you to help Ba in the kitchen. But you shall not do so if it costs over-much patience. Ba has not an even temper. She is not always sweet. And she can be petty. At the present moment she is weak in body too. You will therefore have to summon to your aid all your Christian charity to be able to return largeness against pettiness. And we are truly large only when we are that joyfully.

It was a few months earlier that a relationship had started blossoming between Gandhi and Saraladevi Chaudhurani, who he had met in October 1919, when she and her husband, Rambhuj Dutt Chaudhuri, had hosted him at Lahore. She had sent her son, Deepak, to stay at Sabarmati Ashram. Gandhi felt drawn to her. Meanwhile, her husband too passed away.

Gandhi wrote to Kallenbach, after a two year gap when he could not be located (on Aug 10, 1920),

I have come in closest touch with a lady who often travels with me. Our relationship is indefinable. I call her my spiritual wife. A friend has called it an intellectual wedding. I want you to see her. It was under her roof that I passed several months at Lahore in the Punjab. Mrs. Gandhi is at Ashram. She has aged considerably but she is as brave as ever. She is the same woman you know her with her faults and virtues.

By then, Gandhi had already seen the folly of his relationship, and urged by Devdas, Rajaji and others, he had started disengaging from Saraladevi. In a letter to her in December 1920, he defined spiritual marriage as ‘a partnership between two persons of the opposite sex where the physical is wholly absent. It is therefore possible between brother and sister, father and daughter. It is possible only between two brahmacharis in thought, word and deed…’ He claimed he was ‘unworthy of that companionship’ with her. Saraladevi was not convinced but the communication did not stop completely. Gandhi had suggested the name of her son, Deepak, as a match for Indira Nehru. He, later, married Radha, the daughter of Maganlal. Though Gandhi and Saraladevi were both no more, ‘they had known of this romance.’

What, if anything, Gandhi told Kasturba about the episode is not known, but we must assume that she noticed both the attachment and its severance. Others too would have told her, including Devdas, who was devoted to his mother. We must assume also that the relationship shocked and wounded Kasturba while it lasted, and that its ending enhanced her prestige in circles around him. [Mohandas, Rajmohan Gandhi]

After overcoming this one temptation, which Gandhi refers to in his autobiography and elsewhere, without naming Saraladevi, the relationship with Kasturba kept strengthening over the years. She continued to travel with him, she continued to take part in his struggles, and take care of him as evidenced by this note:

But the most wretched experience was the night journey from Kasgunj to Cawnpore. It was made most uncomfortable by crowds attending at every station. They were everywhere insistent and assertive. The noises they made in order to wake me up were piercing and heart-rending. I was tired. My head was reeling and was badly in want of rest. In vain did Mrs. Gandhi and others plead with the crowds for self-control and silence. The more they implored, the more aggressive the crowds became. It was a tug of war between her and the crowds. The latter would put on the light as often as she put it off. If she put up the shutters the crowd immediately put them down. I was resting did they want me to die a premature death? The answer was, they had come many miles to have darshan and darshan they must have. I had hardened my heart and refused to move till it was daybreak. But there was not a wink of sleep for any of us during the whole of that night. It was a unique demonstration of love run mad. An expectant and believing people groaning under misery and insult believe that I have a message of hope for them. They come from all quarters within walking reach to meet me.

(Young India, 20-10-1920)

If their life together was eventful so far, more than for most other couples, the next two decades were set to be even more turbulent. Having got their personal equation into the best shape after many trials, Gandhi and Kasturba were both ready to completely merge the personal and the political. Their ashrams would continue to emerge as the fountainhead for various constructive programs and political movements which would dismantle an empire.

(To be Continued)