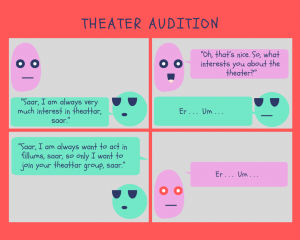

“Saar, I am always very much interest in theattar, saar.”

“Oh, that’s nice. So, what interests you about the theater?”

“Er … Um … Saar, I am always want to act in fillums, saar, so only I want to join your theattar group, saar.”

“Er … Um …”

This conversation snippet, or a variant thereof, is something that many a theater director or theater group founder would have had with quite a few young, self-proclaimed theater aspirants. Far from being frustrated by an incessant stream of such clueless aspirants, we manage to retain a sense of humor at the end of the day and learn to enjoy the various flavors that the same cluelessness comes in:

There’s the guy who mimics this or that Khan from Bollywood so much so that we start worrying whether he might insist on being addressed “Badshah” or “Bhai.” Then, there’s the girl who walks in for a theater audition with a face bearing so much caked-on make-up that the moment she tries to emote, the make-up develop faults lines and starts chipping off. Of course I’m exaggerating, but I hope you get the idea. And then—oh, the horror—how can I forget the typical “gym boys,” who cannot read, think, or emote, but wear super-tight T-shirts to theater auditions, clothes meant to show off the painstakingly chiseled six-pack folds on their abdomens. One can’t help but wonder, if only they had spent half the effort on developing some folds on their brains …!

Please allow me a short digression here: At this point, I’m reminded of what the granddaddy of acting, Constantin Stanislavski, said about the place of unnaturally swollen-out bodies in the theater:

“Do you admire the physique of a circus strong man? For my part I know nothing more repellent than a man with shoulders that more rightly belong on a bull, with muscles that form great Gordian knots all over him. And have you seen these strong men, after their own weight-lifting demonstrations, come out in dress suits leading beautiful horses in the parade? In some ways they are as comical looking as the clowns. Can you imagine these bodies squeezed into the form-fitting costumes of medieval Venice or the snug Renaissance doublet and hose generally worn by the men in Romeo and Juliet? How absurd they would look!

“It is not my province to judge to what extent this physical culture is required in the realm of sport. My only duty is to warn you that the acquisition of such over-development is ordinarily unacceptable in the theater. We need strong, powerful bodies, developed in good proportions, well set up, but without any unnatural excess. The purpose of our gymnastics is to correct and not to swell out the body.

“Now you are at the cross-roads. What direction will you take? Proceed along the line of the muscular development of a weight lifter, or follow the requirements of our art?

Naturally I must direct you along this latter line.

In the past, I used to just redirect such candidates to good film-making workshops and the like and leave it at that. Then, it dawned on me that by doing this, I might be losing out on potentially good theater actors; it could be that no one explained to these youngsters the differences between the mediums, so they chose cinema, by default, and equally by default, just assumed that the theater is just the means—a kind of simulator training—for film acting. I realized that this and other related myths needed some exploding.

So, these days, I first sit them down and explain to them the differences between acting for theater and acting for film so that they can then make an informed choice. (There are also those who eventually learn and understand the basics of both the mediums, and, in turn, develop the required ability to switch their modes of acting according to the medium.)

In this article, I hope to introduce the reader, who could be an acting enthusiast, to some of the important differences between the two mediums of artistic expression.

Note: I would like to add a disclaimer here that although cinema itself is a brilliant medium of artistic expression—with its own set of possibilities, which can dwarf the theater in terms of scale and range—coming as I do from a theater background, in this article, talking about the difference between the two mediums, I would also be pointing out specific aspects in which the modest theater scores over the mighty cinema.

I intend to approach the differences under the following categories:

- General, conceptual differences

- Specific, technical differences (will appear in Part 2 of this article)

General, conceptual differences

At a high level, a few characteristic features are common to both the mediums, such as the following aspects:

- Both are audiovisual in nature (unlike, say, literature).

- Both are narrative forms (unlike, say, music or painting).

- Both involve acting and actors. (Frequently, even the same actors move seamlessly between theater and cinema, adding to the illusion that the two mediums are part of the same continuum. They are not; they are related but essentially separate disciplines.)

These obvious commonalities are perhaps why many people think of them as being two manifestations, flavors, of the same medium, and do not adequately appreciate that they are different mediums, each with its own strengths, limitations, peculiarities, and claims to uniqueness.

The general, conceptual differences between the mediums can be considered broadly under the following heads:

- Product medium vs. performance medium

- Two-dimensional medium vs. three-dimensional medium

- Audiovisual medium vs. audiovisual-sensory experience medium

- Pre-recorded medium vs. real-time medium

- Passive medium vs. active medium

- Director’s medium vs. actor’s medium

Product medium vs. performance medium

A big part of the difference between the two mediums abides in the fact that while cinema is a product, theater is performance.

While there is a product aspect to theater, as well—and hence the phrase to produce a play—and cinema undeniably has several facets of performance, the difference lies in the fact that the performance aspects in cinema are painstakingly designed, executed, and compiled to finally result in a finished whole, after which point, the final product can be run exactly as is any number of times, with zero actual performance or improvisation at run time.

Theater, on the other hand, is all about live performance, in real time, with audiences watching and responding moment by moment, and actors having the choice of accordingly fashioning and fine-tuning their performance ever so gently.

Two-dimensional medium vs. three-dimensional medium

Although both mediums are audiovisual narrative mediums, all said and done, cinema is images beamed on to a flat, two-dimensional screen, with an illusion of the third dimension of depth created through the agency of appropriate cinematography.

By comparison, theater, almost by its very definition, happens on a three-dimensional space, with living, breathing human beings—as compared to images beamed on a screen, as in the case of cinema—inhabiting the actual breadth and depth of the performance space.

Audiovisual medium vs. audiovisual-sensory experience medium

Did I say, a while ago, that both were audiovisual narrative mediums? Let me now introduce a subtle but important, and often overlooked, nuance to that.

But before that, a prevalent wrong notion about the nature of cinema as a medium must be corrected: Many still keep mindlessly repeating the patently erroneous idea that cinema is a visual medium. When was cinema a visual (only) medium? During the silent movies era! As soon as movies became “talkies,” as well, cinema moved from being a merely visual medium to an audiovisual medium proper, and has mostly remained so except for experiments such as the brilliantly conceived and made “Pushpak.”

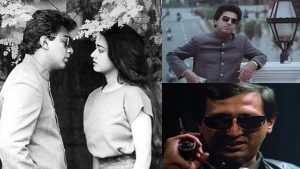

Kamalhaasan, Amala, and Tinnu Anand in “Pushpak”

That settled, now what about the theater? The theater is not only an audiovisual medium but also very much an audiovisual-sensory experience medium. The audience can not only see and hear the performer but even smell and literally sense the human warmth of the actor performing live in front of them, sometimes practically at touching distance.

In some plays, the actor can breach the fourth wall and talk directly to the audience, perhaps even go into the audience area and engage in conversations with audience members, all as part of the ongoing play.

In that sense, theater is indeed that one art form that comes closest to reality, with performer–audience engagement involving and mediated over the most number of sensory inputs possible. It is perhaps this that Oscar Wilde intended when he said the following:

Of course there was no cinema in Oscar Wilde’s times; however, his observation still holds water, nonetheless, because it is a demonstrable fact that the theater can, and often does, engage more senses than any other art form, including cinema.

Pre-recorded medium vs. real-time medium

The fact that theater happens in real time—as compared with cinema, which is pre-recorded—is not merely a factual, technical difference.

This important difference goes down to a crucial aspect of the very experience of artistic moments itself.

Specifically applicable to the Method acting approach, real-time performance means that the performer—while evoking a plethora of emotions in the audience, taking the audience through a roller coaster ride, and ultimately getting them to experience catharsis—is himself or herself also going through the same experiences at the same time. This results in a certain communion, a moment of true human connection, between the artist and the audience, which is unique to theater and remarkably absent in cinema.

In cinema, when your favorite actor is experiencing deep anguish as a certain character on screen, and you tear up, as well, as part of audience, you might want to remind yourself that it is only an image onscreen that is experiencing—nay, representing—deep anguish, and that, in reality, in exactly that moment, the human being who did the acting is very likely in a completely different state of mind, shooting for the next movie, completely oblivious even to your very existence, let alone experience.

What does this mean, philosophically? That there is actually no real, direct human connection made over a shared, common experience of a true emotion, but only an indirect, simulated, somewhat surrogate experience packaged as a product for artistic consumption.

Passive medium vs. active medium

In a certain sense, cinema might have done to the theater what the advent of photography might have done to painting.

While in pre-photography days, a lot of visual art was mimetic in that, while the technique of representation might vary, the purpose was mostly to capture and reproduce the verisimilitude of something or someone, landscape or portrait. However, with the advent of the photo camera rendering the documentation purpose of painting obsolete, visual artists, as a response, might have answered the challenge by going beyond capturing and reproducing reality—which the camera could now do with exceptional ease and efficiency—and into surrealism and other kinds of abstract art, which expects the viewers to engage and exercise their interpretative abilities, as well.

In a similar manner, while the film camera (or the digital camera, in today’s paradigm), with its infinite possibilities, and with help from special effects, can render breathtaking visuals and delicate details in 4K resolution, it also inadvertently pushes its audience into a position of passive consumption of all the visual detail, leaving little to no room for either imagination or interpretation.

The theater, on the other hand, lures the audience to actively participate in the process of art-making. It trains the audience on willing suspension of disbelief and expects them to use their imagination to see the big picture—the vishwaroopa darshanam—in their mind’s eye.

An example is in order: In Perch’s play “Under the Mangosteen Tree,” which is based on Malayalam writer Basheer’s short stories, a young Basheer is seen drawing water from the well and watering his rose garden in the prison.

Iswar Sreekumar as young Basheer in Perch’s “Under the Mangosteen Tree”

The rose plants are just balls of pink cloth laid out on the stage, and the well is just three tires stacked on top of one another, but when the actor tenderly waters the ‘plants’ in absolute truthfulness of emotion, imaginative audiences can actually feel the water droplets. (A 4K recording of actual water droplets falling in slow motion will, any day, pale in comparison to the magic of the non-existent water droplets that could still be felt.)

Suddenly, for the attentive and perceptive theater audience, the entire scene of Basheer’s “mathilugaL” unfurls in the mind as a very personal and intimate experience—a sublime experience that is unique to every audience member but is yet universal in its artistic appeal. This requires the active participation and engagement of a sensitive, imaginative audience.

Thus, the performer in theater does not show everything but plays with the audience, throwing a puzzle now and casting a riddle then, giving the audience both the intellectual kick of the pleasure of discovery and also the emotional rewards thereof. The emotional response and the catharsis are not spoon-fed to the audience—as in the case of cinema (where the audience can passively just consume the images offered to their visual sense)—but will have to be grown and developed by the audience through their active participation in the process.

Director’s medium vs. actor’s medium

It is said that every film is made thrice—first, when the story is conceived and the screenplay is written; then, at the time of production, when the shots are canned; and finally, when the shots are cut, stitched, and assembled on the editing table to form the final narrative. And it is the director who is the captain of the ship, who has a direct say in how the film finally comes out, who has ample creative freedom to do with each actor’s performances as he or she deems fit. For example, the director can chop off significant portions of an actor’s performance at the time of editing, and the actor has practically no say in it—unless the actor happens to be a star and can dictate terms to the director, which, if and when it happens (as it frequently does in the commercial film circuit), would be very inimical to the very integrity of the whole creative process. (Thankfully, there are no stars in theater. There are no heroes, even. There are only actors, protagonists, antagonists, characters, and the like.)

The theater, though, is more of an actor’s medium. Even in the theater, the director is the captain of the ship; however, starting from the time of rehearsals, on realizing that the character has taken root in the actor’s mind, the director gently hands over greater creative control over the character to the actor. Although the actor will, at all times, have to be malleable in order for the director to press the actor in service of the larger vision of the play, the actor on stage definitely enjoys far greater autonomy and dominion over the medium than the actor in front of the camera can ever dream of.

(Specific, technical differences will appear in Part 2 of this article.)

To be continued.